Plato, ‘Gender Ideology,’ and the Efficient Rhetorical Fortress

The Texas A&M mess and what that little story says about the New Right’s comfort with censorship

Recently, I wrote an op-ed in The New York Times about Texas A&M and the inevitable consequences of writing laws that are supposed to accomplish an unconstitutional goal without saying the unconstitutional part out loud. In short, to bring his class in line with a prohibition on course materials that “advocate race or gender ideology,” philosophy professor Martin Peterson could either censor the part of his course that included readings from Plato or he could teach a different class.

When you try to engineer a workaround to the First Amendment, you don’t get “neutral guardrails.” You get prior restraint. And eventually you get something so stupid it should be funny — like university officials treating Plato as a compliance risk. (For those who don’t subscribe to the NYT, the full text of my op-ed is now available on Expression.)

Unfortunately, the response to the piece has been as frustrating as it is predictable.

On the left, the reaction to a free speech argument is increasingly built around what Rikki Schlott and I, in our book The Canceling of the American Mind, called the “Great Untruth of Ad Hominem”: If you can successfully discredit the speaker, you don’t have to grapple with the substance of their speech. So instead of “that’s false,” you get “that’s harmful,” “that’s racist,” “that’s transphobic,” “that’s violence,” “that’s the kind of thing someone with your privilege would say.”

It’s a moral diagnosis masquerading as an argument. And once you’ve redefined disagreement as danger, the campus machinery can do the rest: bias response teams that “support” students by investigating speech, “hostile environment” logic imported into everything, DEI bureaucracies that treat heterodoxy as pathology, and the soft, smiling administrative insistence that they’re not banning ideas — while they quietly make certain ideas professionally radioactive.

What’s been more than a little educational lately is watching the right reach for the same Great Untruth, just with less faculty-lounge polish.

Where the left does it with a kind of graduate-seminar smirk (“problematic,” “harm,” “power”), the right increasingly does it like a grammar-school bully: “pedo scum,” “simps” “corrupted by leftists” “useful idiot,” etc. And when it tries for something closer to “graduate level,” it too often settles for the laziest prefab diagnosis on the shelf: “Trump Derangement Syndrome,” a thought-terminating cliché so tired it should come with a yawn emoji. We just watched Attorney General Pam Bondi toss it at Rep. Thomas Massie in a congressional hearing, as if TDS is an argument rather than a verbal eye-roll in acronym form. Different diction, same move.

On the right, the reaction to this story — in 2026, in Texas, with Republicans very much in charge — has included a new and strangely personal accusation: that I’ve “targeted the right” in order to achieve “mainstream” credibility, and that in doing so I’m “aiding and abetting a left-wing political op so obvious that it is hard to believe that [I’m] not, at some level, in on it.”

More broadly, the claim is that the Texas A&M episode wasn’t really what it looked like, but rather “a pas de deux of malicious compliance,” a “media game,” a kind of kayfabe designed to paint Republicans as censors, with me cast as either dupe or accomplice.

This is especially funny because, if there’s one thing I’ve learned from doing this work for a couple decades, it’s that the left does not hand out “darling of the left” cards to the president of FIRE. Not now, not ever, not on any planet with oxygen. But it’s also clarifying. When your critic’s main move is to declare you spiritually dead and politically captured, it’s usually because they don’t want to grapple with the underlying issue.

And the underlying issue here is pretty simple: The government, through public-university governance, has built a system of prior review for teaching on contested topics. Once you build that system, absurdities aren’t a bug. They’re a feature.

What actually happened at Texas A&M

Let’s start with the obvious: Texas A&M is a public university and public universities are bound by the First Amendment, which is why “we’re just enforcing the law” is not an answer. It’s only the beginning of the constitutional analysis.

In November 2025, the Texas A&M University System’s Board of Regents approved a policy requiring presidential approval for any course that “advocate[s] race or gender ideology, or topics related to sexual orientation or gender identity.”

Focus less on the managerial language and more on what it’s really doing: singling out a set of viewpoints (on race, gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity) for special scrutiny and special restriction on campus. That’s the core First Amendment problem. Viewpoint discrimination — deciding which side of a contested debate can be taught freely and which side needs a permission slip — is a cardinal sin among forms of government censorship.

Yes, there’s also a prior-approval component here, and that matters. But the deeper issue is the state (through a public university system) trying to police ideological content in the classroom while pretending it’s just enforcing “neutral” standards.

According to a report that includes the relevant email chain, Texas A&M philosophy professor Martin Peterson was told he had two options: Remove modules on “race and gender ideology” and “the Plato readings that may include these,” or be reassigned to teach a different class.

The forbidden fruit, in this case, was the Symposium. Specifically, Aristophanes’ Myth of the Androgyne, which is — how do I put this? — not subtle. In the myth, humans originally come in three varieties (male/male, female/female, and male/female), and they’re powerful, happy little spherical creatures until Zeus gets nervous and slices them in half. Ever since, each half wanders the world longing to be reunited with its missing other half — the origin story for desire, love, and the feeling that someone out there is “the one.” It’s weird, funny, cosmological, and ridiculously human, which is why people have been retelling it for 2,400 years.

It’s also why the story shows up, more or less explicitly, in Hedwig and the Angry Inch, where the myth is basically the emotional engine of “The Origin of Love.” And yes, in a moment of cultural-whiplash perfection, one of Hedwig’s creators even popped up in the Times’ reader comments on my essay to talk about it. When your legal regime is so clumsy that it turns Plato into a compliance hazard and drags a Broadway rock musical into a debate about “gender ideology,” you’re not keeping politics out of the classroom. You’re taking a government-approved ideology filter and running it straight through the canon.

And once you create rules that treat certain viewpoints on race, sex, gender, and orientation as presumptively suspect “ideology,” you don’t just chill “advocacy.” You chill discussion. You train administrators to treat anything adjacent to the forbidden topics as radioactive. That’s viewpoint discrimination in practice: not always a neat blacklist, but a system that makes some perspectives — and the texts that naturally lead students to explore them — too risky to touch in ordinary classes.

This wasn’t just one quirky email, either. Reporting indicates that, system-wide, thousands of courses were reviewed and hundreds were flagged, with at least six canceled for “non-compliance.” It’s also worth noting that the university has closed its Women’s and Gender Studies program citing “requirements of System policy and limited student interest in the program based on enrollment over the past several years.” While this could be a reasonable explanation for closing the program, given the larger context, it’s fair to question the university’s motivation.

This isn’t surprising to us at FIRE; we’ve seen how efforts to target disfavored ideas in one arena turn into censorship in others. At Iowa State in 2021, a law that prohibited critical race theory in mandatory staff training was interpreted, incorrectly, to prohibit discussing race or gender in the classroom. Similar confusion happened in Oklahoma, where a law prohibits teaching of certain topics in K-12 classes and in mandatory staff training, but says nothing about academic classes. Still, the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma City Community College dropped requirements and reviewed course material in response. And now courses are being cancelled across public entire university systems within Texas.

‘Plato isn’t banned’ and other comforting non-arguments

A bunch of the criticism from the right has taken the form of what I can only describe as not actually an argument.

The most popular version is: “Plato isn’t banned at Texas A&M.” One right-leaning piece even emphasizes that Plato is assigned in other courses, as if the question is whether Plato has been legally outlawed across the entire zip code.

But my claim, and the reason this story matters, was never “no one at Texas A&M may read Plato ever again.” The claim is: In a core curriculum course, a professor was told to remove readings from Plato’s Symposium in connection with a module on gender (or be reassigned), in the context of a state-driven policy requiring prior approval for courses that “advocate” certain ideas.

If your response is “well, students can still read Plato somewhere else,” you have not defended academic freedom. You’ve defended rationing. You’ve defended the idea that public-university teaching on contested topics should happen only where administrators pre-clear it.

Another version of the non-argument is the “set-up” story: This was “malicious compliance,” the professor and department leadership were trying to embarrass Republicans, and anyone who reports it is being played. That framing has been published explicitly.

Even if we grant the “malicious compliance” premise for the sake of discussion, it still doesn’t solve the First Amendment problem. The Constitution does not contain a “your motives are annoying” exception. The question is whether the state can impose prior review and viewpoint-based restrictions on classroom instruction at public universities. “It was bait” is not a legal theory. You are still not required to take the bait.

The ‘Efficient Rhetorical Fortress,’ now with a new Trump 47 paint job

We can describe this in the framework I’ve used for a while now, which comes from my and Rikki Schlott’s book The Canceling of the American Mind: the Perfect Rhetorical Fortress, the Efficient Rhetorical Fortress, and No Man’s Land.

The Perfect Rhetorical Fortress is the left’s “heads I win, tails you’re evil” machine. If you oppose a policy, it’s not because you have a different view of tradeoffs or constitutional limits; it’s because you’re racist, sexist, transphobic, or acting on behalf of oppressive structures. If the facts don’t fit, the PRF doesn’t collapse. It expands. The objection becomes proof of your moral contamination. Add a little “harm” language, a little “safety” language, and you’ve got the modern campus version of an unbeatable argument: not because it’s correct, but because it’s designed to be immune to correction.

For an in-depth analysis of the PRF at work, check out my piece, “Abigail Shrier versus the Perfect Rhetorical Fortress,” published back in 2024. (This was the most popular ERI piece for a long time, only recently edged out by “The situation for free speech in Europe is even worse than I thought” from last month.)

The Efficient Rhetorical Fortress is the New Right’s equal-and-opposite defense against argument. It’s partly the result of backlash, partly imitation, and partly sheer muscle memory after years of watching the PRF win fights. The ERF doesn’t accuse you of being “problematic.” It accuses you of being a traitor, a sellout, a RINO, a coward, a tool, part of “the regime.” Where the PRF wraps itself in moral concern, the ERF wraps itself in tribal loyalty. Different aesthetics, same logic: If you disagree, you’re not simply wrong, you’re persona non grata.

And then there’s No Man’s Land: the place where any attempt to have an actual argument gets you shelled from both sides. You try to say something like, “Universities have had a serious left-wing illiberalism problem for years, but government censorship is still unconstitutional and dangerous,” and you get hit by the PRF (“why are you defending harm?”) and the ERF (“why are you attacking our side?”) simultaneously. It’s an obstacle course of whataboutism and purity traps, and the goal is to exhaust anyone who insists on principles that apply consistently.

You can see the fortress dynamic at work in the response to the Texas A&M story. If the state builds a regime that singles out certain viewpoints — on race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity — for special scrutiny and special restriction, and the predictable result is chilled teaching and censored syllabi, the normal response in a liberal society is: “Maybe we shouldn’t be doing viewpoint discrimination at public universities.” The fortress response is different. The fortress says, “It can’t be censorship, because we are the anti-censorship people. Therefore it must be a trick. It must be malicious compliance. You’re being played. And if you’re not being played, you’ve transformed.” The facts are not allowed to update the belief, the belief updates the “facts.”

This move is psychologically soothing, rhetorically convenient, and substantively empty. It’s also — and this is the part I can’t resist — eerily Foucauldian. Not in the “let me cite French theorists at you” sense, but in the deeper, grimmer sense: the assumption that power decides what’s real. That the point of institutions isn’t truth-seeking but domination. That the only thing that matters is which coalition controls the levers, and therefore our side can’t be doing censorship because our side is the aggrieved party. They have all the power. We have all the victimhood. Therefore anything we do is not coercion but “restoration.”

The same logic that says “speech is violence” on the left becomes “it’s not censorship when we do it” on the right.

That’s not liberalism. Liberalism is the annoying discipline of saying, “Even when we’re sure we’re right — even when we’re sure they’re wrong — we still don’t get to use the state to enforce orthodoxy.” It’s the boring, miracle-working idea that we build rules for ourselves precisely because we cannot trust ourselves when we’re angry, frightened, or morally certain.

The rhetorical fortresses are what you build when you don’t want rules, but power. And when you start using them to justify viewpoint discrimination at public universities, you’re not defending free speech. You’re just picking a different censor and calling it justice.

Why this is easier than admitting what’s happened to the GOP and free speech

Here’s the uncomfortable truth that helps explain the denial: Acknowledging the Texas A&M problem requires acknowledging something larger.

A lot of people on the right don’t want to admit how much the GOP — especially Trump-world — has drifted from “free speech” as a principle into “free speech, but only when it flatters us.” And once you’ve made that pivot, stories like Texas A&M become psychologically dangerous. If you admit the state is doing viewpoint discrimination in the classroom, you’re one step away from admitting your own team has gotten awfully comfortable using power — legal, regulatory, and quasi-legal — to punish speech and speakers it dislikes.

Start with the most obvious category: lawsuits as intimidation theater. Trump sued The New York Times for $15 billion over coverage he claims interfered with the 2024 election. He sued The Wall Street Journal (and Rupert Murdoch, and others) for $10 billion over reporting about an alleged letter connected to Jeffrey Epstein. And then there’s the Ann Selzer case — because yes, we now live in a country where a president sues a pollster for producing poll results he doesn’t like.

And that’s just the courtroom side. There’s also the regulatory-pressure side, which is where the “this is technically legal” crowd tends to go quiet, because it’s always easier to defend a threat than a statute.

In the last month alone we got a near-perfect example of how speech chills without anyone needing to pass a new censorship law. Stephen Colbert says CBS lawyers refused to air an interview with Texas Democratic Senate candidate James Talarico; Colbert speculated the network was motivated by a fear of the economic impact of FCC Chairman Brendan Carr’s proposed re-interpretation of the“equal time” rule. This is something Colbert explicitly framed as politically-driven pressure, and something major outlets have reported as part of a broader concern about the FCC policing media speech. Colbert’s solution — posting the interview online — was clever, but the larger point is bleak: When lawyers start treating ordinary political conversation as a compliance hazard, the chilling effect has already done its work.

Then there’s the overt retaliation against the legal profession itself — the “You’ll represent the people I dislike over there? Cool, enjoy losing your clearances and your access” move. Trump’s executive orders targeting major law firms — Jenner & Block, WilmerHale, Perkins Coie, Susman Godfrey, Paul Weiss, and others — were explicitly framed as punishment for political associations, adversarial hires, or litigation choices, and multiple firms sued. Courts have repeatedly treated these orders as constitutionally suspect, with judges blocking or striking them down. That is not “draining the swamp.” That is the government leaning on the adversarial system — one of the core engines of accountability in a liberal democracy.

And yes, the cultural side matters too, because it shows how the same posture is normalized outside the courthouse. Trump has publicly cheered suspensions of late-night hosts, egged networks on in their censorial tactics, and even floated threats of lawsuits against networks in that same ecosystem. You can call this “just trolling” if you want. But it’s always “just trolling” until a regulator, a merger review, a licensing posture, or a government contract quietly enters the chat.

Put it all together — lawsuits against media institutions, lawsuits against pollsters, regulatory saber-rattling that makes network lawyers flinch, executive orders aimed at punishing law firms for who they represent — and the throughline becomes hard to ignore: This isn’t a movement that reliably says, “The government must stay out of the business of punishing speech.”

You can still believe universities have been hostile to conservatives (they have been and they are). You can still believe DEI bureaucracies have warped hiring, teaching, and institutional courage (all true). I do, and haven’t been shy about saying it over the years.

But if your response is to let the state decide which viewpoints are permissible in the classroom — and then to deny its censorship because the targets are the right enemies — you’ve decided to fight illiberalism with illiberalism. And that is exactly how you end up with Plato getting fed into a compliance grinder.

Where I land, and where I’m not moving

Let me reassure everyone tempted by the “Lukianoff has transformed” fan fiction: I am not exactly getting love letters from Michael Hobbes or Jason Stanley right now either. Tom Hanks and Beyoncé have not invited me into the Illuminati. If there’s a secret handshake, nobody taught it to me. If anything, my superpower remains the ability to irritate the left by refusing to retire a sentence I’ve been repeating for twenty years: Higher ed is in serious trouble, and it has been for a long time.

The left’s institutional speech culture didn’t magically heal because Texas Republicans decided to go on a crusade against “woke.” We’ve still got the machinery that treats heterodox speech as a safety hazard. We’ve still got administrators who prefer investigations to arguments. In 2023 and 2024, campus deplatforming attempts spiked.

So no, I’m not here to pretend campuses are fine. They’re not. If you want me to say universities have become more ideological, more punitive, and more performatively moralistic over the last decade — and that this has done real damage to academic freedom and to knowledge creation — you’re in luck, because I have been saying exactly that for most of my adult life.

But the right also has to face facts.

You don’t fix illiberalism by importing it into the statehouse and then pouring it into public universities. You don’t defend free speech by building a viewpoint-discrimination regime and calling it “reform.” And you don’t get to wave away the constitutional problem by insisting the people pointing it out must be secretly left-wing, or that they’re “in on it,” or that it’s all some elaborate “media game.”

If your solution to campus orthodoxy is “let the government decide what can be taught,” you haven’t found a cure. You’ve just swapped out censors and asked us to pretend it’s liberty because you like the new one better.

I’m not moving on that. Not for the left, not for the right, and not for any imaginary cabal with better parties than the ones I actually get invited to.

SHOT FOR THE ROAD

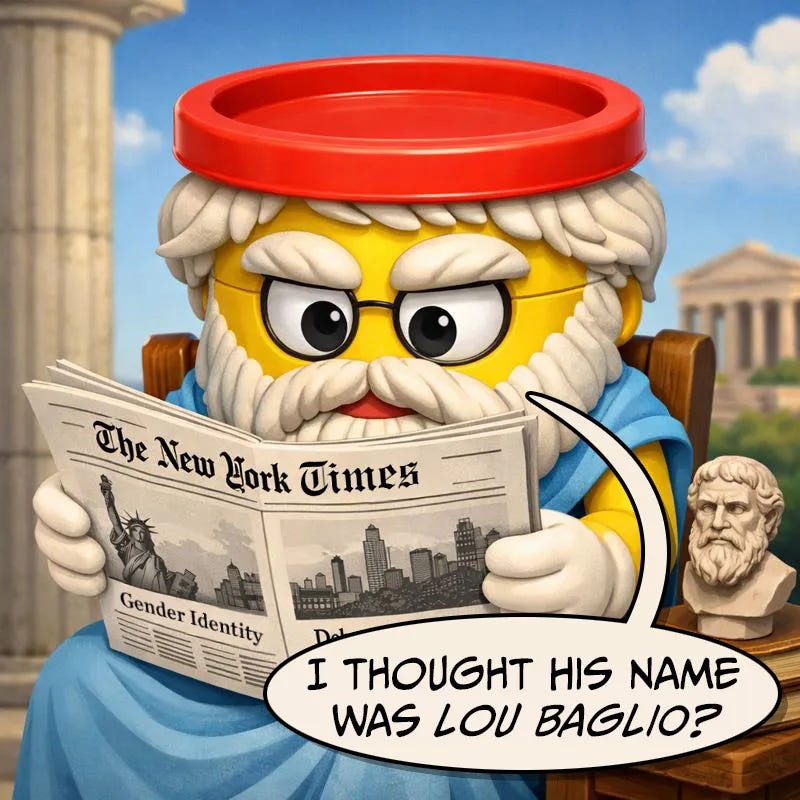

Ladies and gentlemen, I have been memed.

It came to my attention recently that an off-the-cuff comment I made on X went viral, and screenshots began appearing all over the internet as a meme. I’m flattered, obviously, but I also just want to say to the Internet Gods — and, specifically, Instagram user @iamthirtyaf: I have much better jokes!

But alas, as ERI Managing Editor Angel Eduardo said, “It’s never our darlings that get the golden ticket.”

This is a clear headed and even handed takedown of the illicit tactics of both the Left and Right partisans. This is why I donate monthly to FIRE - you and FIRE are doing important work (that used to be done by the ACLU before they got taken over by the Wokesters). Thank you for this piece!

great work as usual, sir. i am grateful FIRE is holding the line.