Trump vs. Law Firms

And why it might be the most anti-free speech thing the president has done

“It was nearly impossible to get anyone on camera for this story, because of the fear now running through our system of justice.”

Scott Pelley opened his 60 Minutes report on the Trump administration’s bullying of law firms with this remarkable sentence — telling us that in a profession of professional talkers, he found very few willing to talk. In fact, only one of the sources Pelley spoke to for that segment is currently working at a law firm being targeted, even though there are, collectively, thousands of lawyers at those firms. We know that count because the lawyers’ names are on the firms’ websites.

Of the many things the Trump administration has done in the last 100-and-change days that have impacted free speech, the threats to law firms might be the most troubling. This concern stems from high-minded reasons of liberty (of course!) but also because it is “personal” to FIRE. FIRE is effectively a law firm — one that is currently in court with the president. If the president can simply revoke our access to courthouses, for example, it will become very difficult for FIRE to oppose the government on anything.

Accordingly, FIRE joined amicus briefs in the four lawsuits brought by targeted firms (so far). And recently in one of those, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia permanently enjoined the administration from enforcing its executive order. This is a good sign, but we’re still well within the danger zone.

In keeping with that, we’d like to take this opportunity to talk about what the Trump Administration has been doing to law firms. It’s important for everyone to really understand what’s going on here and why it matters to all of us.

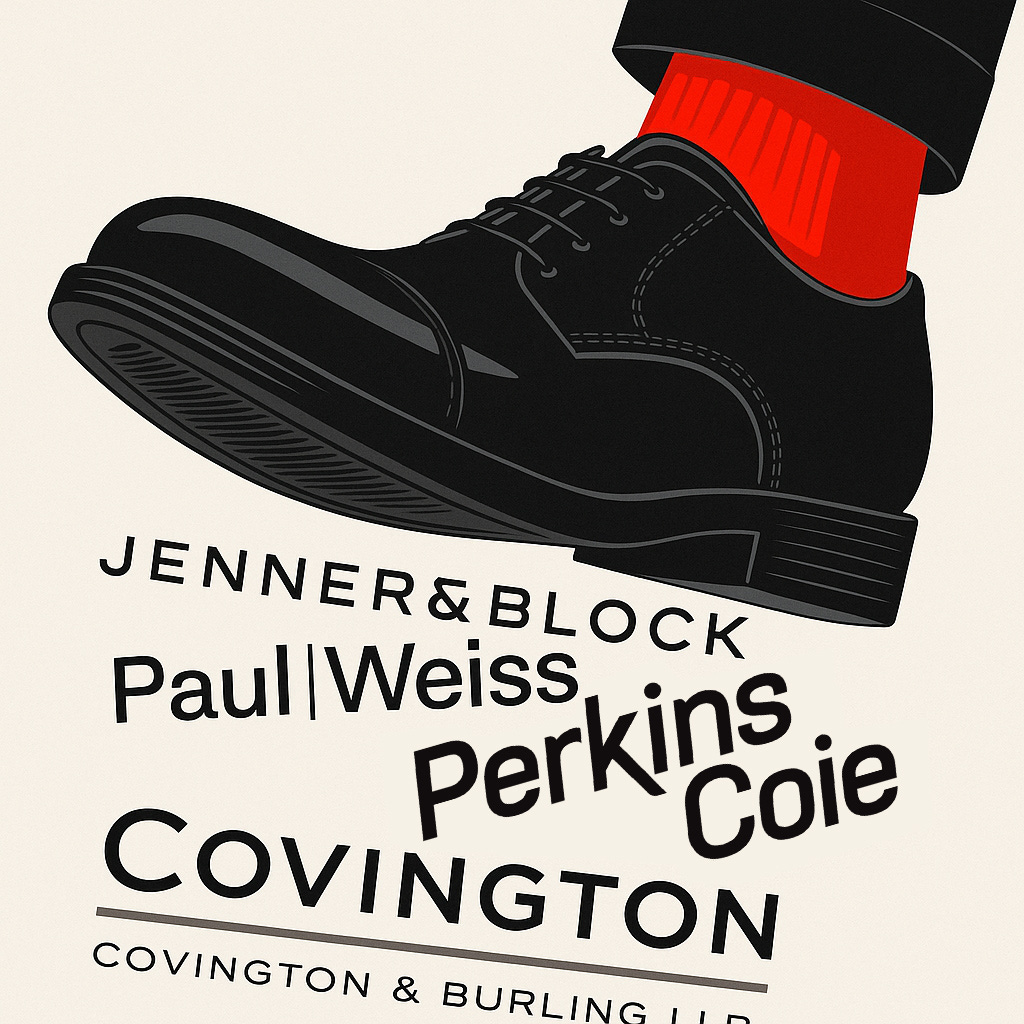

The Trump administration’s targeting of law firms looks retaliatory

Long story short: Seven firms involved in cases that the Trump administration didn’t like were targeted by orders and memoranda from President Trump himself in what appears to be retaliation for their involvement in those cases. Those firms face (or faced) having their government contracts reviewed, the actual or potential revocation of security clearances from their attorneys, and their attorneys’ access to federal buildings limited.

(In addition, a total of twenty law firms received an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission request for information about employment practices that might have discriminated against candidates on the basis of their race in violation of Title VII. We’ll come back to the EEOC letters later.)

The firms targeted by executive orders and memoranda seem to stand accused of…being lawyers. That is, providing representation to someone who needed it. When you look at the orders and memoranda (the difference between an executive order and an executive memorandum seems to lie in formalities, not substance, so we’re just calling them “the orders” from here on out) the firms are being targeted for:

Working for Special Counsel Jack Smith, who investigated allegations regarding the President’s role in the January 6 Capitol riot and mishandling of classified documents;

Working for the Hillary Clinton campaign and having subcontracted for the creation of the “Steele dossier,” a 35-page political opposition research document that contained unverified allegations of Russian collusion (this rationale applied to two targeted firms — the firm that was contracted, and the firm a former partner started after he left);

Working to overturn voter ID laws as part of an effort funded by George Soros;

Having been the previous workplace of someone who left to join the Manhattan District Attorney’s office during its investigation of hush money payments to Stormy Daniels; and

Working for (or being) Special Counsel Robert Muller, who investigated Russian interference in the 2016 election.

We don’t have to speculate about these motives; they’re written in the orders. One requires a little context. The firm Susman Godfrey, which is accused of “spearhead[ing] efforts to weaponize the American legal system and degrade the quality of American elections,” represented Dominion Voting Systems in civil lawsuits against people and media outlets who claimed the their voting machines, used in places during the 2020 election cycle, were rigged.

Some lawyers, like Mark Elias, Andrew Weissmann and Peter Koski, were targeted by name. Others were included in a hand-wave; one order, for example, targets “all members, partners, and employees… who assisted former Special Counsel Jack Smith.”

What’s most important to note is that the sanctions in the orders would hamstring the work of the firms in question. The revocation of security clearances would make it impossible for lawyers to see classified evidence in a case. While for some attorneys that might not be that big of a deal, it’s a pretty big deal when the orders target attorneys because of their involvement in prior cases with classified evidence, like the special counsel investigations.

But worse still is the potential loss of access to federal buildings, which these orders call for.

Federal courthouses are federal buildings. And while we are not aware of any lawyers having lost access to courthouses as of yet, it seems to be a potential outcome. The government’s position, as quoted in the Perkins Coie opinion, is that barring attorneys from entering federal buildings isn’t a big deal because during COVID, “nobody was entering federal buildings; nobody was meeting; all access and all communications were handled via letter, email, phone calls.”

Meanwhile, during COVID:

Given that, during COVID, nobody entered courthouses, either, the term “federal buildings” does seem to include them. Judge Beryl A. Howell of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, who would later grant a permanent injunction against Trump’s order targeting law firm Perkins Coie, made the same speculation during the hearing for a temporary restraining order. As ABC News reports:

At one point in the hearing, the judge raised concern over the provision of the executive order that aims to restrict Perkins Coie from having access to federal buildings. That would, Howell noted, presumably include every federal courthouse in the country [...]

“I want to make sure — you had no trouble getting into this building today?” Howell asked.

Even if we could be convinced alternative methods of communication were always an acceptable substitute to in-person attendance of being at a meeting, hearing, or trial, the government’s position ignores the message that this ban would send to potential clients. How many clients are likely to hire a firm that the government has banned from the federal buildings where their meetings, hearings, or even trials might take place?

If the administration felt that opposing lawyers were filing briefs that they knew or should have known did not hold merit, the administration should have sought sanctions from the judge in the case and potentially from the state bars that license those attorneys. In other words, if the oft-repeated claim about the “weaponization of government” held true, retaliatory executive orders wouldn’t be the way to oppose that.

A president attempting to sanction law firms for nothing more than providing representation to opposing parties undermines the rule of law by acting as an implicit threat to law firms: Help the people who disagree with me, and you’re an enemy of the United States. (That’s true even if the “opposing party” the firm or its lawyers helped was… the United States, under a prior administration — as in the cases of Special Counsels Jack Smith and Robert Mueller. It’s like the Spider-Man pointing meme, except there’s only one Spider-Man, and he’s pointing at himself.)

Even without squinting, these orders look a great deal like an attempt to censor the lawyers and law firms they are targeting. That’s how the Perkins Coie order looked to Judge Howell, who wrote in her opinion accompanying an order granting the permanent injunction:

Using the powers of the federal government to target lawyers for their representation of clients … in an overt attempt to suppress and punish certain viewpoints, however, is contrary to the Constitution, which requires that the government respond to dissenting or unpopular speech or ideas with “tolerance, not coercion.” The Supreme Court has long made clear that “no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics . . . or other matters of opinion.” Simply put, government officials “cannot . . . use the power of the State to punish or suppress disfavored expression.”

That, however, is exactly what is happening here.

(Citations omitted.)

Exactly what is happening with the EEOC investigation is harder to say. If the EEOC believes based on its investigation that these firms have violated Title VII (which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, sex, national origin, or religion), and the issue can’t be resolved cooperatively, the EEOC can bring a lawsuit. But the EEOC isn’t entitled to any special deference in its interpretation of Title VII, and courts seem to be where the administration’s novel interpretation of the law goes to die.

Nevertheless, the EEOC letters seem to be exerting a coercive force on the firms which received them. How much of that force is fear of the administration, and how much of it is concern about prior hiring practices, is impossible to say. Eight of the nine firms that have reached agreements with the administration are in the group of letter recipients. Additionally, Skadden (which settled) and DLA Piper (which has not) ended their employee affinity groups after receiving the letter.

The Trump administration has been clear about its motives in the orders

If we were ever to embark on an adventure devoted to trying to undermine the Constitution and the rule of law, we would be sorely tempted to hide it. But looking through what the administration has actually done to target law firms is remarkable, primarily due to the total lack of artifice about it. The memoranda, executive orders, and EEOC letters spell out their purpose plain as day.

For example, a February 25 memorandum targeted Covington & Burling by “suspend[ing] any active security clearances held by Peter Koski and all members, partners, and employees of Covington & Burling LLP who assisted former Special Counsel Jack Smith.” Covington does not appear to have responded in any public way to the memorandum.

Another example: A March 6 order targeted Perkins Coie for, among other things, “work[ing] with activist donors including George Soros to judicially overturn popular, necessary, and democratically enacted election laws, including those requiring voter identification,” and for hiring Fusion GPS to prepare the Steele dossier on behalf of the 2016 Clinton campaign. On March 11, Perkins Coie sued; on May 2, they were granted summary judgment and a permanent injunction.

On March 17, acting EEOC Chair Andrea Lucas sent 20 law firms requests for information about their DEI practices. By mid-April The New York Times reported that eight of the firms who received these letters had reached agreements with the White House. WilmerHale and Perkins Coie, who were also targeted by executive orders, are on the list of 20 firms.

A March 20 order targeted Paul Weiss for, among other things, “hir[ing] unethical attorney Mark Pomerantz, who had previously left Paul Weiss to join the Manhattan District Attorney's office solely to manufacture a prosecution against [the president].” That order was withdrawn the next day after Paul Weiss struck a deal with the White House, promising $40 million in pro bono work “to support the Administration’s initiatives, including: assisting our Nation’s veterans, fairness in the Justice System, the President’s Task Force to Combat Antisemitism, and other mutually agreed projects.” It isn’t clear who the client or clients will be for those services.

Meanwhile, a March 22 memorandum titled “Preventing Abuses of the Legal System and the Federal Court” took a slightly different approach, directing the Attorney General to review law firm activity for misconduct or violations of the rules of professional responsibility. But it targets the Elias Law Group by using, as its opening example of alleged misconduct, the role founder Marc Elias allegedly played in the creation of the Steele Dossier back when he was a partner at Perkins Coie — a position he left in 2021 to start the Elias Law Group. Attorneys from the Elias Law Group signed an open letter opposing Trump’s orders, and Marc Elias appeared in the 60 Minutes report.

A March 25 order targeted Jenner & Block for, among other things, “obvious partisan representations to achieve political ends” and “re-hir[ing] the unethical Andrew Weissmann after his time engaging in partisan prosecution as part of Robert Mueller's entirely unjustified investigation.” Jenner & Block sued on March 28 and got a temporary restraining order. They are seeking a permanent injunction.

A March 27 executive order targeted WilmerHale for, among other things, “reward[ing] Robert Mueller and his colleagues…by welcoming them to the firm after they wielded the power of the Federal Government to lead one of the most partisan investigations in American history.” The next day, WilmerHale sued and got a temporary restraining order; that TRO did not apply to the revocation of security clearances, however. On May 9th, two WilmerHale attorneys had their security clearances suspended pursuant to the order. WilmerHale is seeking a permanent injunction.

An April 9 executive order targeted Susman Godfrey for, among other things, working to “degrade the quality of American elections” and “fund[ing] groups that engage in dangerous efforts to undermine the effectiveness of the United States military through the injection of political and radical ideology.” Two days later, Susman Godfrey sued and got a temporary restraining order. And they, too, are seeking a permanent injunction.

We have had a month of quiet since the Susman Godfrey order, and speculation as to whether this is the first tranche of what will become many more. For the moment, it seems the administration has refocused on colleges again, particularly Harvard. Harvard sued the administration in April, but so far, the four firms identified as representing Harvard haven’t been targeted. (Nor, to be fair, has FIRE been targeted so far, despite our representation of pollster Ann Selzer in Trump’s lawsuit against her.)

Lawyers and law firms are essential guardians of civil rights and civil liberties

Civil rights, including the right to freedom of speech, sometimes must be defended in court. But access to courts is not enough. As Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland explained, “The right to be heard would be, in many cases, of little avail if it did not comprehend the right to be heard by counsel. Even the intelligent and educated layman has small and sometimes no skill in the science of law.” The work of courts is so specialized, and at times so counterintuitive, that only a professional can truly offer the most effective representation.

That is, after all, why they have law schools. It’s why the government provides lawyers to criminal defendants who can’t afford them. It’s also why FIRE has litigators. Lawyers and law firms are as important to the protection of civil rights as doctors and medical practices are to the protection of health. Having a non-lawyer represent you in court is like taking medical advice from something you saw on TikTok — we aren’t saying it definitely won’t work, but in most cases, things are more likely to get worse than better.

Because law firms are (like it or not) essential to vindicating our rights, a government attack on law firms is really an attack on those rights. If Perkins Coie could be punished for having represented someone who disagreed with the government’s interpretation of voting rights, it would not stop there. Law firms would be targeted for representing people who disagreed about abortion rights, gun rights, and speech rights just as easily. And it would no longer matter what the Constitution or its amendments said. Fortunately, so far, every judge that has considered these orders has enjoined them.

Hopefully, we have seen the last of these executive orders. If not, FIRE will be there, as it always is. As we’ve said before, we are loyal to principle, not people or parties — and as always, our principle has been and remains: If it’s protected, we will defend it. No exceptions. No throat-clearing. No apologies.

And if you understand and value the work we do, we encourage you to support it. Donating to FIRE is offering direct support to the fight for free expression in our courts, on our campuses, and in our culture at large.

SHOT FOR THE ROAD

I’m very excited to announce that “The War On Words: 10 Arguments Against Free Speech—And Why They Fail” by me and FIRE Senior Fellow Nadine Strossen will be released on July 1. Nadine is one of my life-long heroes — she was president of the national ACLU when I was in law school — and the opportunity to co-author a book with her was beyond my imagination when I went to work for the ACLU of Northern California after law school. And if I had imagined it, I doubt I would have imagined it would come out as well as this book did. It features rebuttals to 10 anti-free speech myths and canards that refuse to die. It’s a must-have for anyone defending free speech these days, and a must read for anyone who thinks those 10 arguments are right (because they are so, so wrong).

So which half of the legal profession should I be concerned for, the half that can bearly stomach me, or the half that actively hates me?

Leonard Levy in a 1999 book that is very well worth reading these days (Origins of the Bill of Rights) emphasized crucial truths about our First Amendment rights and freedoms. Sadly, such self-evident truths have become, as John Stuart Mill put it, "dead dogma." Too often too many speak and think of the First Amendment as if its scant words somehow created or defined the freedom of speech and press and the right to assemble and petition. Levy highlighted the egregious error of such thought and speech.

"In a sense, the constitutional guarantee of freedom of the press" and speech and the rights to assemble and petition "signified nothing new. It did not augment or expand freedom of the press" and speech or the right to assemble and petition government. The First Amendment's declarations regarding the freedom of speech and press and the rights to assemble and petition the government merely "recognized and perpetuated an existing condition."

Clearly, well before the First Amendment was written or ratified, our original Constitution established that all "Government in the United States derived from the people, who reserved a right to alter it, and [all] government was accountable to the people. That required a broader legal concept of freedom of the press" and speech than existed previously. "Thus freedom of the press" (and speech) "meant the right to criticize harshly the government, its officers, and its policies as well as to comment on matters of public concern."

"The scope of the amendment," most fundamentally and crucially, "is determined by the nature of the government and its relation to the people." Absolutely all American "government is the people's servant, exists by their consent and for their benefit, and is constitutionally limited" by the people and is "responsible" to the people. Our Constitution confirmed that in America, the people are the only true "sovereigns;" the people are not the "subjects" of any "master." The "protections" of our Constitution are "indispensable" for "the development of free people in a free society;" they "are not to be the playthings of momentary majorities" or of any public servant in any branch of any level of government.