Burning down the library: How AI laws are reviving the worst ideas of campus censorship

AND my new book, 'The War On Words,' with the great Nadine Strossen is officially out today!

One of the more frustrating things about working on free speech for over two decades is watching the same bad ideas come back wearing slightly different outfits. It’s like déjà vu, but with better fonts. Dealing with them over and over again can be tiring, but doing so remains incredibly important — particularly when it comes to AI.

In the National Review yesterday, my FIRE colleague and ERI contributor Adam Goldstein and I wrote about how new state laws aimed at “preventing discrimination” in artificial intelligence are quietly setting the stage for something we’ve seen many times before: speech codes.

Followers of FIRE and ERI will be very familiar with speech codes. These were policies enacted by colleges and universities, dating back at least four decades, designed to restrict certain kinds of speech on campus. And more often than not, they used “anti-discrimination” as their rationale. Recent regulations proposed and imposed in multiple U.S. states are also invoking “anti-discrimination” — only this time, it’s for technologies that seek to define objective reality itself.

These laws — already passed in states like Texas and Colorado — require AI developers to make sure their models don’t produce “discriminatory” outputs. And of course, superficially, this sounds like a noble endeavor. After all, who wants discrimination? The problem, however, is that while invidious discriminatory action in, say, loan approval should be condemned, discriminatory knowledge is an idea that is rightfully foreign. In fact, it should freak us out.

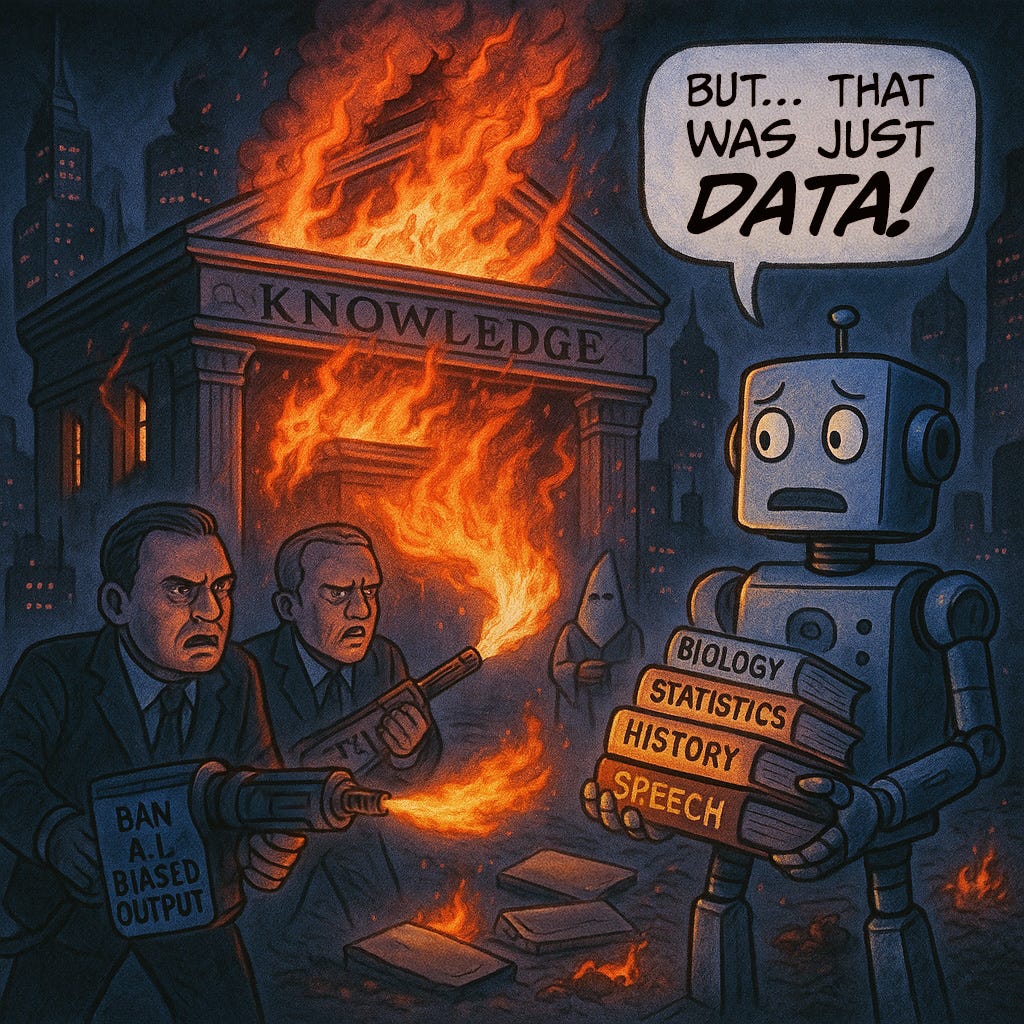

One point Adam and I make in our National Review piece is that, rather than calling for the arrest of a Klansman who engages in hateful crimes, these regulations say you need to burn down the library where he supposedly learned his hateful ideas. Not even just the books he read, mind you, but the library itself, which is full of other knowledge that would now be restricted for everyone else.

This cannot be allowed. Knowledge needs to be free to develop and be disseminated regardless of whether or not we like what we find. This is a matter of serious epistemic consequence. If knowledge is riddled with distortions or omissions as a result of political considerations, nobody will trust it. In fact, that’s one of the big problems we find ourselves in today with so many of our knowledge-creating institutions. Many, many people see them as fundamentally biased and politically-motivated, and as a result do not trust them.

And as I’ve argued many times before — including in The Canceling of the American Mind with my co-author Rikki Schlott — there are good reasons why they shouldn’t.

The first time around: speech codes and the anti-discrimination argument

Way back in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, campuses started adopting “anti-discrimination” speech codes. The rationale was simple and emotionally compelling: certain kinds of speech make marginalized students feel unwelcome or unsafe, and therefore should be restricted. The word “safety” did a lot of work. So did “inclusion.” But the big hammer was always “discrimination.”

When FIRE was founded in 1999, we saw how these policies — often vague, and usually overbroad — were used to punish everything from off-color jokes to dissenting opinions to simple statements of fact. Over time, the assumption hardened: If it could be interpreted as fuel for discrimination by even the least charitable listener, it shouldn’t be said.

Too many folks in left-dominated spaces have no natural immunity to this attack. And it’s understandable in many ways. People don’t want to seem racist, sexist, or transphobic, and they don’t want to be even adjacent to someone who might be accused of any of those things. So they fold. They pre-censor themselves and, through chilling, others. And they subject dissenters to the full brunt of their social opprobrium. They nod along with things they don’t actually believe, rewrite facts to sound more palatable, and deal with the dissonance quietly and internally.

Sometimes, they even go so far as to call that “progress.”

Now Playing: Speech Codes II — The AI Frontier

Fast-forward to 2024. Lawmakers in Texas and Colorado have decided that AI shouldn’t generate biased outputs. In other words, this technology shouldn’t be used to produce “discriminatory” content, results, or responses. Again, on the surface, this seems like a good idea — after all, we don’t want a future where your smart fridge denies you ice because of your zip code, or gives you some hateful screed about Jews when you ask it a question about European history.

But these laws don’t just target deliberate discrimination. In Colorado’s case, intent doesn’t matter at all. It’s about outcomes. And that’s where things get really hairy. If, for example, an AI model produces different results about different demographic groups on a given question — even if it’s because the data shows that those groups actually behave differently in the real world — decisions based on it could be flagged as discriminatory. And that brings with it potential sanctions, fines, and other costly acts of discipline against the developers of these technologies.

The result? To cover their asses, developers will train their models to avoid anything that could be interpreted as unequal or discriminatory. And given how nebulous that term can be, that can include modifying or even eliminating quite a lot of valuable facts and information — uncomfortable truths about humanity and society, objective data, and even reality itself. AI developers will pre-censor the output of their technologies. They will produce results and disseminate information that doesn’t actually align with reality. They will rewrite or reframe facts to sound more palatable. They will leave us uninformed about the nature of the world around us, and totally unaware that this is the case.

And in many cases, some will go so far as to call this “progress.”

If this sounds remarkably similar to the effects of campus speech codes, welcome to the club.

We should care about the consequences of these AI regulation bills

The same psychological and cultural forces that justified censorship on campus are now being baked into the systems we’re going to rely on to search for information, make decisions, and understand the world around us. If those systems are trained to treat certain conclusions as off-limits — not because they’re wrong, but because they might make someone uncomfortable — we’re in deep trouble, morally, culturally, and epistemically.

I go deeper into this in my piece from back in January on HB1709, also known as “The Responsible AI Governance Act” or TRAIGA.

The important thing here is that this isn’t about whether discrimination exists (of course it does). It’s not even about whether we should combat it (of course we should). It’s about whether the best way to do that is by making truth feel taboo.

Nobody wants to be anywhere near the sin of discrimination — especially racial discrimination. That’s a noble impulse, and quite the cultural evolution from even fifty years ago. It’s a great sign that we find it so reprehensible that people will do backflips to avoid even the appearance of it. But when that instinct becomes so strong that we start reshaping reality, we’re not helping anyone. We’re just making ourselves — and now, our machines — less accurate, less honest, and less effective in navigating the world as it really is.

If we continue this trend, we will be manufacturing an epistemic crisis that will be unprecedented in its scope and scale. Our budding AI technologies will inevitably become the primary source and manufacturer of the world’s information. If that information is tarnished or tampered with to spare our feelings — especially if it’s done pre-emptively — there will be no changing or correcting course, because our map, our compass, and even our intuitions will be completely wrong.

SHOT FOR THE ROAD

Ladies and germs, it has arrived!

The War On Words: 10 Arguments Against Free Speech — And Why They Fail, which I had the honor and pleasure of co-authoring with FIRE Senior Fellow, former ACLU president, and personal hero of mine Nadine Strossen, is out today!

In this book, we cover ten of the worst and most exhausting (Nadine would, in her infinite patience and charity, opt for saying “the most common and persistent”) arguments against free speech and in favor of censorship — including “Words are violence,” “Hate speech isn’t free speech,” and the infamous “You can’t shout ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater.”

I consider it a truly handy guide for responding to these terrible (Nadine says “popular”!) arguments in your own life. Pick it up now wherever you get your books!

And in case you missed my Substack Live Q&A with Nadine that we did earlier this month to celebrate the book’s release, you can check it out right here:

Companies are so terrified of potential bias lawsuits that they're essentially lobotomizing their models.

Greg is right but his team never provided a framework for how. His profile and role is different.

Knowledge became a product thru patents and copyrights and legal papers.

We need to incentivize knowledge production so we created a capitalistic structure around it just like goods and services.

If anyone has an answer on how to untangle it, would be good to hear it.