How state AI regulations threaten innovation, free speech, and knowledge creation

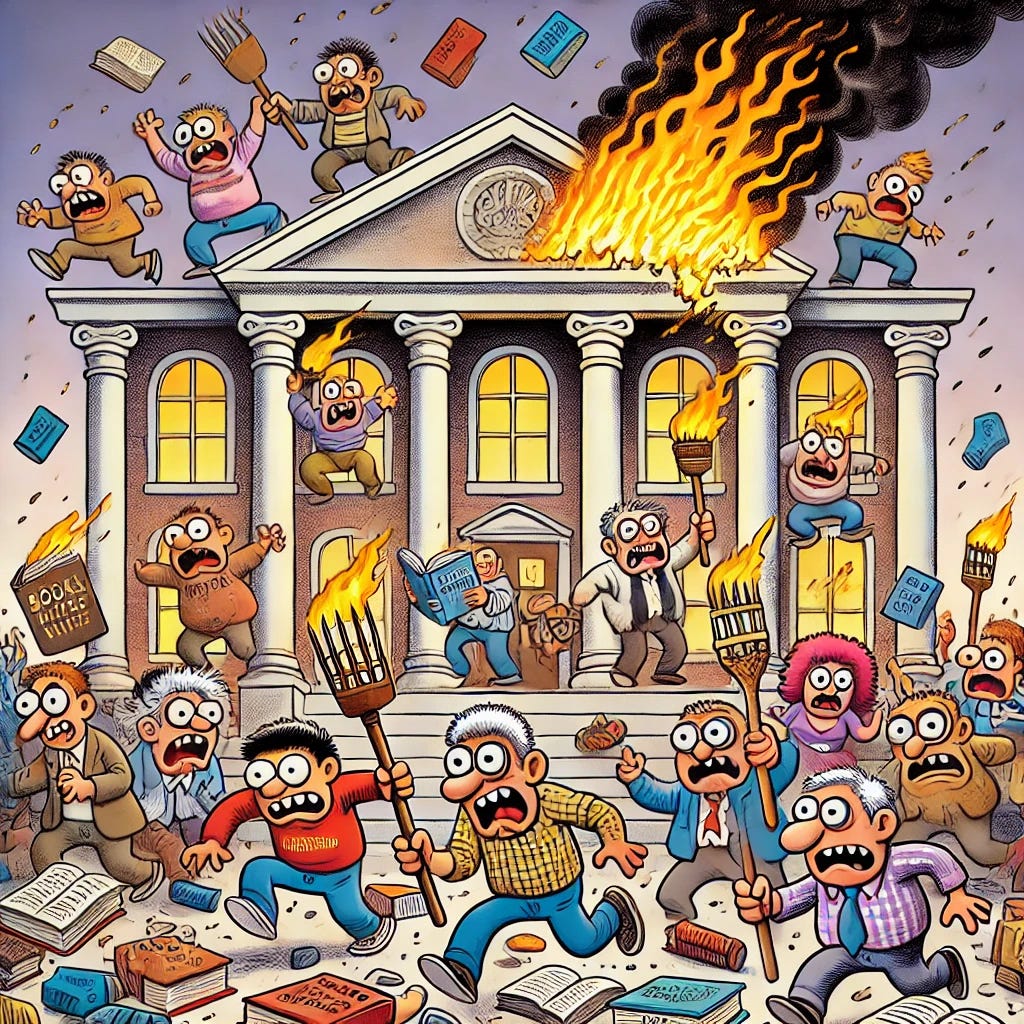

While they may be intended to prevent harm, these regulations are like punishing the library for the book a bigot read rather than punishing the bigot himself.

Picture a world where, rather than simply punishing a bigot for discriminating against a couple on the basis of race, the authorities target the local library instead.

See, when they did an investigation, the authorities noticed the bigot had checked out a number of books that clearly inspired and informed his actions. As a result, they decided the library must be punished for providing them.

In fact, the authorities decide to take it one step further: punishing the publishing house that printed the books. As a result, all copies are confiscated, the library and publisher are hit with fines, and legislation is drafted to prevent the books from being printed, disseminated, or read by anyone else ever again.

If this seems bizarre and wrong to you, it should. And your mind shouldn’t change when we swap out libraries and book publishers with artificial intelligence systems. After all, the underlying point is the same: it is wrong to punish a provider of information for the things people do with it.

Unfortunately, more than a dozen U.S. states are considering exactly that. Inspired by the European Union’s pro-censorship technology regulations, many laws are currently being drafted in America that would hold developers and users alike responsible for “discriminatory” information drawn from AI systems. Such short-sighted policies will lead to almost unlimited government entanglement with the production of knowledge, incentivizing LLM companies to corral their technologies to avoid lawsuits and fines.

About five years ago, AI was narrow, meaning it was limited in its capacity and scope. Systems would be built to identify faces or screen loan applications, for example. Now, however, AI systems are broad — and getting broader. Language models like ChatGPT and Claude are poised to become among the primary, if not the primary, means of producing and consuming information across a variety of networks, industries, and platforms.

And no matter how anyone feels about it, the genie can’t be put back in the bottle. AI systems will soon become the way we learn about the world. Given their immense capability and wide application, these systems will also inevitably undergird commerce, science, government services, medicine, technological advancement, and more. They will lead to new discoveries and inventions. They will uncover new knowledge at a fraction of the speed and cost of current systems. And as with so many technologies before it, they will destabilize the current order and threaten those in power.

As Greg has mentioned before, disruptive technologies have a tendency to introduce new and often scary problems. But we cannot lose sight of the good that comes along with those innovations, which have historically been worth the trouble. The printing press, for example, resulted in a dramatic escalation in the European witch trials and two centuries of bloody religious conflict. But it also revolutionized our ability to communicate, discover and engage with knowledge, and champion principles that we modern-day humans take for granted: free expression, free inquiry, and open discourse. It is no exaggeration to say that modern society as we know it would not exist if not for Gutenberg’s miraculous machine.

However, this doesn’t mean we do nothing about the issues that arise as a result of new technologies. The trick is to react in ways that are conducive to progress. In the 1990s, America crafted a bipartisan, pro-innovation national policy vision that gave rise to the internet and the Digital Revolution. U.S. firms and consumers continue to benefit from that wise policy paradigm today and, thanks to it, American innovators are already leaders in AI and advanced computation.

Unfortunately, the “algorithmic discrimination” laws working their way through U.S. state legislatures this spring are doomed to have the opposite effect. By melding the worst elements of the current European digital technology regulation with the outgoing Biden administration’s social justice fundamentalism-focused AI agenda, these laws are direct assaults on the free expression of Americans everywhere. This of course includes academic freedom, free inquiry, and knowledge creation — all of which fall under the umbrella of free expression.

And while these proposed regulations may be intended to prevent harm, they’re much more like punishing the library for the book a bigot read instead of punishing the bigot himself.

A state patchwork as national AI policy

The Biden administration’s approach to AI regulation was outlined in a historically long AI executive order, along with a so-called “AI Bill of Rights” and a number of other policy documents. The underlying idea in these documents was that algorithmic systems are “unsafe, ineffective, or biased” and “deeply harmful,” such that they needed to be heavily controlled by design.

And while Biden’s administration is now behind us, their fear-based policy animates the AI bills currently being coordinated by what’s called the Multistate AI Policymaker Working Group, which brings together over 200 unnamed lawmakers from more than 45 states to meet in private and hammer out the details for comprehensive state regulation of what they call “algorithmic discrimination.”

Sponsors of these bills regularly justify their support for these measures by noting how Congress is moving slowly on AI policy, while the sponsors themselves are making progress. Colorado was first to pass one of these measures with its bill SB 205. Like the many proposed bills that have followed it, SB 205 mirrors the European Union’s AI Act in its insistence on preemptive compliance procedures for AI developers, users of AI products, and others in the AI supply chain. Similar bills have been introduced in California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Mexico, New York, and Virginia, among others.

SB 205 and the many lookalikes across other states regulate the use of “AI,” broadly defined to include much modern software, when “automated decision making” is used in “high-risk” use cases. Those use cases include any time AI is used as a “substantial factor” in making a “consequential decision” — which is any decision that affects the terms, price, or a consumer’s access to services in areas like employment, education, legal services, financial services, insurance, utilities, government services, and in some cases much more. Covered industries vary by state, but almost all the bills cover these areas.

Any covered business that uses an AI system as a substantial factor in a “consequential decision” must write and implement a risk management plan, and create an algorithmic impact assessment for every covered use case of AI. Developers who make AI products or services that could be used as substantial factors in “consequential decisions” are subject to transparency requirements, so that businesses using their products can write their compliance documents. They are also subject to monitoring requirements and have to write a risk management plan of their own.

In some states, small businesses would be exempted, while in other states the law would apply to everyone — including individual users acting in a personal capacity. All parties — developer and deployer — also face the possibility of negligence liability for any instances of “algorithmic discrimination.” Of course, there are also fees and penalties that the state governments can impose.

Longtime ERI readers will remember Greg discussing Texas HB 1709, also known as the “Texas Responsible AI Governance Act” or TRAIGA, which adopts the sort of technocratic, top-down regulatory micromanagement already undermining digital technology innovation in Europe. As Greg outlined in that piece, TRAIGA’s primary method for countering discrimination is through imposing penalties for “negligence” on the part of AI developers, distributors, and even some users. The bill also requires the writing and constant updating of compliance documentation in the form of “High-Risk Reports,” “Risk Identification and Management Policies,” and “Impact Assessments,” which would end up becoming a full-time job.

All of this would be overseen by the Texas Artificial Intelligence Council, which Dean has previously described as the most powerful AI regulator in America, and therefore among the most powerful in the world. This council would be granted the power to ensure the “ethical development and deployment of AI” which, as Dean points out, is sure to become captured by special interests who will lobby for socially suboptimal policies.

It’s clear that elements of the European approach to AI regulation are now being imported to the U.S. in the form of a state-by-state regulatory patchwork of AI mandates. AI companies are already under tremendous pressure to adjust the kinds of data and information they produce in the name of AI alignment. These kinds of hoops and restrictions will only increase that pressure, and also cause them to adjust the data and information they ingest as well.

Given the nature of our cultural and technological landscape, this will almost certainly result in an even greater oversampling of politically biased interpretations of data, based on who currently controls the levers of power. Since many of the state laws being pushed are remnants of the Biden administration’s AI regulation efforts, it would be no surprise if that bias leans towards social justice fundamentalism-oriented ideas. But as we’ve seen in the first two months of the Trump administration, that pendulum can swing violently in the other direction as well.

Either way, the result is extensive government entanglement with these systems, which will cause AI companies to politicize, distort, or disguise basic facts to shield themselves from liability. Ultimately, this will also lead to a collapse of trust in the knowledge supposedly produced by AI, severely compromising our ability to know the world as it is, and to generate knowledge in ways that benefit society.

AI regulations as algorithmic precrime units

Among other issues, these new state AI regulatory measures would lead to groups of bureaucrats whose sole task would be to weed out examples of AI “discrimination” before it happens. Think of it as a kind of Algorithmic Precrime Division, akin to the Precrime police in the 2002 film “Minority Report,” and the Phillip K. Dick novella upon which it’s based.

In the name of building “safeguards” against potential harms, the Multistate AI Policymaker Working Group model legislation requires that developers and deployers “use reasonable care to protect consumers from any known or reasonably foreseeable risks of algorithmic discrimination.”

The risk of negligence liability for algorithmic discrimination means that AI systems will almost surely be censored by their creators to avoid lawsuits. And the “algorithmic impact assessments” required for developers and corporate users will be far more than just a paperwork requirement. Namely, they will result in:

Massively centralized AI adoption plans. Given the risks of noncompliance with these laws’ broad definitions of “algorithmic discrimination,” especially to larger firms, adoption of generalist AI will need to be centralized. Management will be able to tolerate very little to no employee- or team-level experimentation, which severely threatens the potential of this new technology to produce knowledge, aid in scientific and medical research, and facilitate technological innovation.

Overly risk-averse culture. Obviously, implementing an AI adoption plan that forces businesses to hyperfocus on all conceivable future harms will encourage risk aversion. Creating a centralized process within firms will also make it likelier that AI use cases will be reviewed by broad committees of “internal stakeholders,” all of whom will have their own boutique complaints, job loss fears, biases, and anti-AI sentiments. Committees are also, by their nature, more likely to add an additional degree of risk aversion.

Inflexible AI use policies. Once an adoption plan is in place, businesses will be unwilling to change their strategies incrementally. Changes could require new compliance paperwork, for example, and businesses are likely to err on the side of caution or inaction rather than go to the trouble. This may cause them to stick with one “AI strategy,” even if it is ineffective or detrimental, because attempting to change it would be too costly.

Employee surveillance. To ensure that employees do not use AI in ways that could run afoul of the laws (or of the firms’ own legally mandated compliance plans), employee use of AI — and perhaps even of their computers more broadly — could be even more thoroughly monitored by management. This would also severely limit the expressive and experimental uses of this new technology, and hobble all the potential progress that could be made through ingenuity and discovery.

Decreased AI diffusion. As technology expert Jeffrey Ding has pointed out, centralized plans for adoption of general-purpose technologies tend to hinder what’s called the “diffusion” of those technologies. Diffusion is defined as “the process through which technology spreads among firms in the market.” In other words, it’s how societies get the benefits of novel technologies, such as enhanced worker productivity, new downstream inventions, novel business practices, and the like. There is little point to new general-purpose technologies if they can’t be thoroughly diffused. In his book, “Technology and the Rise of Great Powers: How Diffusion Shapes Economic Competition,” Ding has also argued that the economies that diffuse technologies the most successfully outperform those that merely innovate.

Given the similarity of these U.S. bills to the EU AI Act, it is reasonable to gauge the impact of these algorithmic discrimination bills by using conservative estimates of the AI Act’s compliance costs. The Center for European Policy Studies — the European analogue of the Brookings Institution — estimated that the AI Act could add as much as 17% to any corporate spending on AI (either in development or deployment).

Though they note that they project the more normal compliance cost to be more like 5-15% of overall AI spending, it is worth pointing out that this estimate was conducted before ChatGPT hit the market. In other words, this estimate was determined assuming that most AI systems would have narrow purposes (hiring algorithms, facial recognition, etc.) rather than millions of conceivable general-purpose uses. The widespread use of language models like ChatGPT could meaningfully raise these compliance cost estimates, making these regulations even more of a financial burden for organizations and institutions using AI technologies. The effect on this increased burden on knowledge production, technological innovation, and diffusion should be obvious.

A few states appear to be getting the message and rethinking European-style AI regulation. Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin (R) recently vetoed a major AI regulatory measure that got to his desk, and the Texas sponsor of TRAIGA floated a significantly overhauled version of the bill.

How algorithms are already regulated

Another thing that makes this aggressive push for preemptive AI constraints so perplexing is that its advocates ignore the many existing federal and state laws and regulations already on the books addressing discrimination and consumer harm. In fact, everything they fear about algorithmic systems is already covered by many layers of law.

In April 2023, four major federal law enforcement agencies — the Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission — issued a “Joint Statement on Enforcement Efforts Against Discrimination and Bias in Automated Systems.” The agency heads made it clear that, “[e]xisting legal authorities apply to the use of automated systems and innovative new technologies just as they apply to other practices.”

A year later, these agencies and five others issued an even broader “Joint Statement on Enforcement of Civil Rights, Fair Competition, Consumer Protection, and Equal Opportunity Laws in Automated Systems,” in which they pledged “to vigorously use our collective authorities to protect individuals’ rights regardless of whether legal violations occur through traditional means or advanced technologies.” FTC Chair Lina Khan summed up these agency efforts even more simply: “There is no AI exemption to the laws on the books.”

Whatever one thinks of the many different laws and regulations already covering algorithmic systems, what matters is that they exist, and their coverage is indeed quite sweeping. Even left-leaning groups, who tend to be the most vocal proponents of anti-discrimination regulations on AI, acknowledge the extensive existing remedies that already cover many AI applications.

States also have many duplicative layers of these same regulations in place. For example, the Texas code includes provisions addressing discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodations, as well as extensive regulations and penalties for unfair and deceptive practices. Every other state currently considering similar social justice fundamentalism-focused AI bills possess the same remedies for discrimination and consumer harms.

All these policies are also supplemented by various court-based remedies, as well as America’s overly-litigious tort system. Indeed, AI developers are already being subjected to a variety of lawsuits, including in the copyright arena.

There is simply no shortage of overlapping discrimination and consumer harm policies at the federal and state level that will govern the algorithmically-generated harms that advocates of these new laws are concerned about. Moreover, these broadly-applicable standards are complemented by many layers of sector-specific bureaucracies and regulations, which govern industries where AI will be used to aid in the development of drugs, medical devices, automobiles, aircrafts, financial instruments, and other products.

In some cases, algorithmic or autonomous systems are already being overly regulated by these bureaucracies and technocratic regulations. It’s difficult to imagine how and why we need even more of it.

How the proposed AI regulations also put free speech at stake

Nico Perrino, FIRE’s Executive Vice President and host of the So to Speak podcast, has said that AI is “the arena where the next great fight for free speech will be fought.” We couldn’t agree more.

Indeed, FIRE has warned of the chilling effect on speech associated with these measures, as well as the potential for mass censorship of generative AI in particular. In testimony before the House Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government last February, Greg expressed his concerns regarding how “[a] regulatory panic could result in a small number of Americans deciding for everyone else what speech, ideas, and even questions are permitted in the name of ‘safety’ or ‘alignment.’”

During the hearing, Greg was intent on emphasizing not just the threat AI regulations pose to free speech, but also the threats regulatory capture and a government oligopoly on AI pose to the creation of knowledge itself. The legislation being proposed in various U.S. states at the moment significantly increases government involvement in the knowledge creation process. This is incredibly dangerous because, as we know from history (and as Greg mentioned in his talk late last year at the Russell Kirk Center), those in power tend to bristle when they lose their grip on controlling knowledge:

Allowing people to be free to think as they will, and to say what they think, is a radical idea. And it is opposed in every generation because it turns out that when given the chance, people end up having a lot of questions for authority. Authority doesn’t like that. This is why, as Frederick Douglass once put it, the right of free speech “is the dread of tyrants.”

But it’s not just the dread of tyrants within kingdoms or churches. It’s also the dread of tyrants over supposed knowledge — the ones who think all important truths are known and, as it happens, they are the first in history to know them! What luck!

What’s more, the kind of government entanglement with knowledge creation being proposed is unlikely to stay where it starts. We’ve learned from experience on campus, where FIRE’s expertise is at its greatest, that regulations initially justified for narrow purposes, like ensuring equity in women’s sports, were quickly weaponized against free speech itself — as seen with Title IX’s expansion into regulating expression.

Undoubtedly, these proposed AI regulations will empower the same forces that undermined knowledge creation, academic freedom, and free expression in higher education and journalism these last two decades (or more) to shape AI in ways that align with the sacred beliefs of their ideological orthodoxy. It will also place the government — or at least a small number of activists empowered by the government — in the role of arbiters of truth. This is a situation whose dangers shouldn’t require explanation. If it terrifies you to picture your ideological opponents exerting influence on what AI can be used for, do, and produce, it should make you think twice about wanting that kind of power for yourself.

Laws and regulations have a function, but stifling expression can’t be one of them

We aren’t against setting up reasonable guardrails and systems to avoid the kinds of harms our technologies can cause. States can, should, and in fact do combat existing and well-documented problems resulting from AI systems, like deepfakes and fraud. They can even combat so-called “algorithmic discrimination” when it occurs by using a wide range of existing state and federal laws.

What makes the bills we have described here problematic is their focus on preemptive regulation of potential harms — and worse yet, by punishing not the perpetrators of those harms, but information providers. This approach might make sense in the halls of a state capitol, to those who would gleefully wield these regulations to shape the world and knowledge as they see fit. But outside the halls of power, these regulations would have very real and very serious consequences.

It is not just “innovation” that is threatened. It is also freedom of speech and thought, academic freedom and free inquiry, and perhaps most importantly of all, the ability to produce knowledge.

These laws incentivize developers to avoid any controversial outputs from their models, which will make them constitutionally averse to the very kinds of experimentation and innovation that lead to leaps in knowledge, understanding, and technological advancement. This will also fundamentally undermine the diffusion of any advancements that do occur, because of the way these laws create barriers among businesses to the adoption of AI.

In fact, one thing that the government can do is create a national framework for AI policy that can prevent state and local regulations from going too far. As Adam recently wrote in a piece for The Hill:

Congress should comprehensively preempt state and local AI regulations that impinge upon interstate algorithmic commerce and speech. Even Colorado’s Polis has called for Congress to craft “a needed cohesive federal approach . . . to limit and preempt varied compliance burdens on innovators and ensure a level playing field across state lines.” Short of full-blown preemption, federal lawmakers could craft an “AI learning period moratorium” that would limit new federal and state AI regulatory mandates that undermine a competitive national marketplace. This would give AI entrepreneurs some breathing room to launch bold new ideas and products to meet the rising global competition, while policymakers study which policies make sense. Some issues or sectors covered by traditional state authority will need to be carved out, including education and law enforcement. But Congress can take steps to clarify what AI models and applications are covered by federal laws.

Innovation, freedom, knowledge creation, and diffusion have been the recipe for American technology dominance in decades past. AI has the potential to usher us into a new era of innovation and progress on a variety of fronts, many of which we can scarcely imagine right now. But if America adopts these proposed Multistate AI Policymaker Working Group laws, it will devastate our country’s economy, technology, science, medicine, discourse, and ability to generate knowledge. What’s more, we will fall behind countries that adopt far more permissive approaches to handling AI, eliminating our capacity to compete on the world stage.

We have run with new technologies in the past, rolled with the punches, and allowed ourselves to generate vast amounts of knowledge and innovation. We must hold fast and continue that trend with artificial intelligence. If we don’t, others will, and we’ll all be worse off for it.

Dean W. Ball is a Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center and author of the newsletter Hyperdimensional.

Adam Thierer is a Senior Research Fellow at the R Street Institute and the author of “Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom.”

SHOT FOR THE ROAD

I had a blast with John Avlon on The Bulwark’s “How to Fix It” podcast. We talked about the Trump administration’s escalating war on free speech, “what happens when universities stop defending debate,” and the paperback release of Rikki Schlott & my latest book, “The Canceling of the American Mind” due out April 29!

The more "safe" we make AI, the more dangerous it becomes. Not because safety is bad—but because it becomes a cover for who gets to define truth.

The systems being regulated are already designed by entities that filter, shape, and gatekeep knowledge—without democratic consent.

https://plaintxtdecoded.ghost.io/reflections-not-revelations/