Footnotes to the recent New York Times piece on FIRE

And a response to Jason Stanley’s claim that the crisis on campus for the last 10 years has been a “moral panic”

Over the weekend, much to my surprise, there was a very good article featuring FIRE on the front page of The New York Times.

We knew the article was coming, but given that we’ve occasionally had, shall we say, mixed treatment by Times, I was a little anxious about it. But seeing it, I was very pleased at how fair I thought it was towards our work.

The theme I hit the most in my interview for the article was simply this: There are some people who are perceiving a shift in what FIRE has done, but they seem to have missed that we’ve defended against all threats to freedom of speech — from the right, left, and WTF — since day one. We appreciate that people are starting to notice this principled defense, but as I’ve written before, the secret motto of FIRE since its earliest days has been We’d rather drive this bus into a wall than be unprincipled.

Still, despite it being good overall, there were a few things in the article that warrant a response.

On FIRE’s treatment of religious schools, and schools in Florida

Contrary to what the Times piece implies, I don’t believe our approach to religious schools has been at all gentle. For example, we have fought Georgetown on its free speech violations before, and have done the same for many other religious schools time and time again.

What we do recognize is that our religious schools have the associational freedom to decide not prioritize free speech. This, by the way, earns them a “Warning School” label from FIRE, which really gets us a ton of criticism — particularly from right-leaning schools like Hillsdale College.

Also, regarding the Times’ questioning why “some public universities in Florida get sterling ratings [on FIRE’s College Free Speech Rankings] despite adherence to that state’s Stop WOKE Act,” the answer is twofold:

First, we did not want to blame the schools for a state law they were required to comply with [Edit: To clarify, we would penalize schools that passed policies or punished students and faculty consistent with the Stop WOKE act or any other unconstitutional state law, but the existence of such a law by itself did not merit an automatic penalty].

Second, and most importantly — and this should have gotten a mention in the Times piece — we didn’t merely “vigorously oppose” the Stop WOKE Act, we defeated it in court (at least so far, the case is currently on appeal)!

On the Yale costume controversy

The Times piece also made mention of the now-infamous 2015 campus controversy at Yale involving Nicholas and Erika Christakis, offensive Halloween costumes, and some pretty irate students.

If you aren’t sure what I’m talking about, or just need a refresher, FIRE covered the incident extensively. There’s also video of the confrontation between Christakis and the Yale students (which I recorded myself, by the way).

Just to be clear, the controversy wasn’t actually about insensitive costumes being worn at Yale. It was about an email warning students against considering them. Like any good product of the 1960s free speech movement, Erika Christakis disseminated a thoughtful response to that email, arguing for student autonomy and the ability to navigate controversy without the help of authority. I encourage you all to read it. It was that totally reasonable call for maturity and self-sufficiency that set students off.

We’re coming up on ten years since the Yale incident, and I may end up writing something more substantial about it here. Stay tuned for that.

‘Down on the AAUP?’ Yeah, you know me.

Another thing worth mentioning is the Times’ description of the acrimony between FIRE and the American Association of University Professors — or maybe more accurately, between me and some of the AAUP’s leadership.

Regular ERI readers will know that I addressed that controversy and laid out my unrestrained thoughts on the AAUP in a post back in November 2024.

The Times article characterizes the conflict as primarily about Alex Morey’s response to AAUP president Todd Wolfson’s explicitly partisan response to the 2024 election results, but the reality is that my issues with the AAUP are much deeper than that.

As Will Creeley, FIRE’s fearless legal director, mentioned in the Times piece, FIRE has a general principle of not attacking other nonprofits — but there are two caveats: We will respond if we are attacked, and we will speak out if we believe the organization has become a threat to free speech or academic freedom.

As I argue in my own article on the topic, the AAUP has done both.

There isn’t much to add beyond those 5,000+ words, but I would be remiss if I didn’t comment on one last thing:

While we were waiting for the Times article to come out, Wolfson decided to do an interview with Inside Higher Ed, I guess to dispel any lingering doubts about whether or not they’ve become an unquestionably partisan left-leaning organization.

In that interview, Wolfson first decries the Trump administration and Chris Rufo for developing the “imaginary” narrative that academia is full of “Marxist ideologues indoctrinating our students.” He continues by saying he is “working on a policy vision that will move us into the midterms” which he says will be “a counterimaginary of higher ed.”

Then, he says his organization is part of the “progressive community,” calls for a general strike a la 1919, and apparently declares the official foreign policy of the AAUP by saying “We believe strongly that no weapons should be sent to Israel, at all. Not defensive or offensive, nothing.”

This was almost comical to read. If you’re trying to convince people that you aren’t Marxist ideologues, you probably shouldn’t sound like a Bolshevist calling for a “general strike,” talk about professors like they’re the proletariat, self-identify with the “progressive community,” or establish a foreign policy that just so happens to be popular with the far left on campus.

The irony of this is clearly lost on Wolfson, which pretty much wraps a bow on the point I’ve been making overall.

As I told the Times, if higher-ed had listened to us 15 years ago about the ideological takeover of college campuses, the Trump administration’s actions against them right now wouldn’t be happening.

So when the Times says that I have called out the AAUP for “help[ing to] plunge academia into crisis” — yeah, I have, because they did.

And speaking of that…

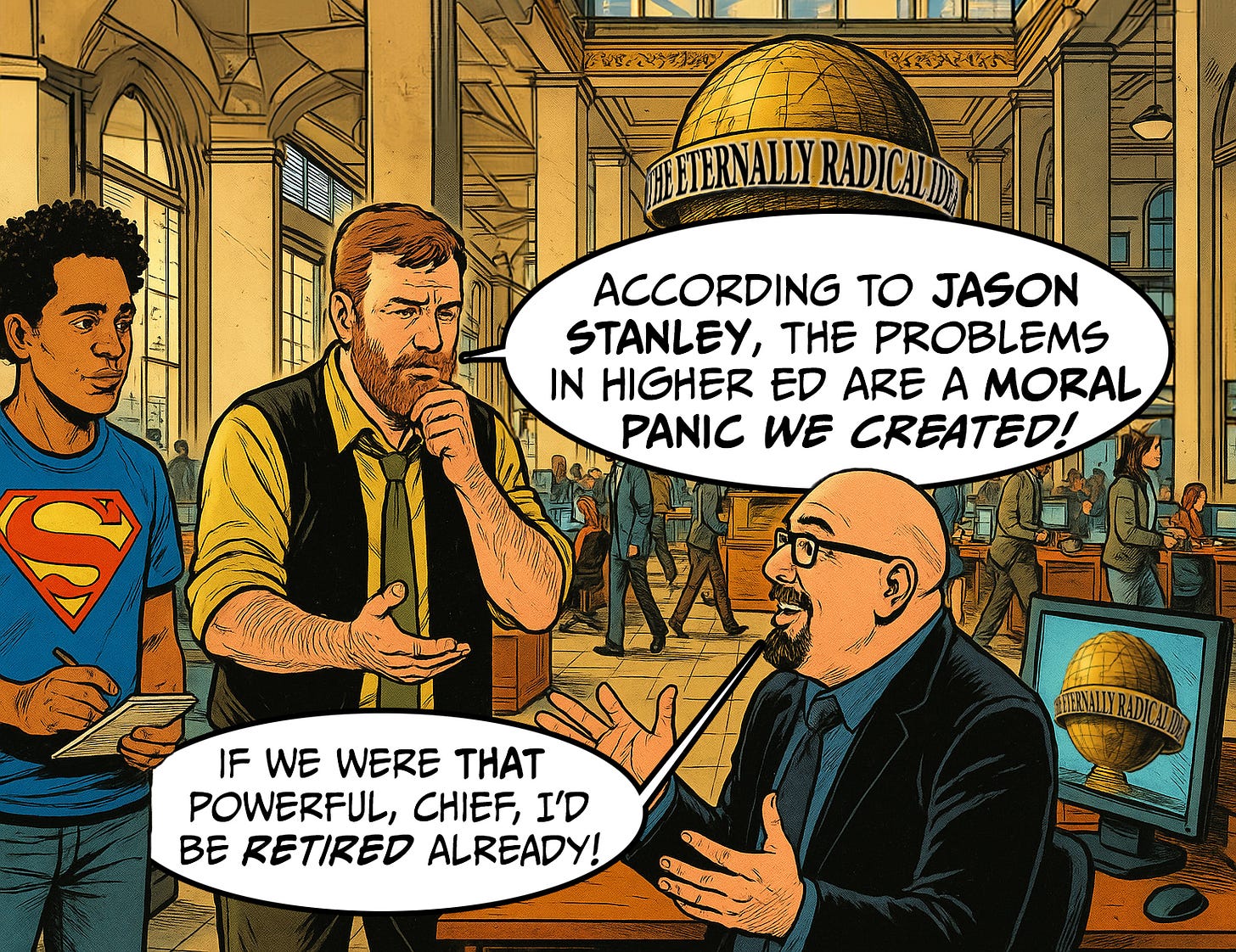

The ‘moral panic’ of professor Jason Stanley

It’s been a while since I’d heard the name Jason Stanley, but he popped up in the Times article with some pretty typical commentary: accusing FIRE of helping to “create a road map for the Trump administration’s current campaign against higher education.”

Oh boy.

As some of you may remember, Jason Stanley was the Yale philosophy professor who made a big show of fleeing to Canada in the months following Trump’s second inauguration, citing concerns about fascism and anti-Semitism on campus. I guess it’s to his credit that, unlike many others who made the same pronouncements, Stanley actually went through with it. He now teaches at the University of Toronto.

He was even the subject of a splashy article in Vanity Fair for his escape from the States, which he called an “impulsive” decision prompted by Columbia University’s capitulation to the Trump administration (which, by the way, FIRE also criticized). The whole thing seemed just so self-aggrandizing — as if this philosophy professor genuinely believed the first thing Trump would say to himself upon seizing power would be “Now I must destroy my arch nemesis: The Great Jason Stanley!”

Having read Stanley’s books, including How Fascism Works, he doesn’t really make much of a distinction between fascism and right-wing authoritarianism, but the differences matter. In short, fascism was a weird melding of left-wing and right-wing ideas, combining nationalism, racism, and socialism in a way that won more adherents than it ever should have — especially among intellectuals and, distressingly, on German campuses. Meanwhile, right-wing authoritarianism is basically the story of the human race prior to the 20th century, when left-wing authoritarianism started to become more prominent.

It’s also super funny that Stanley’s chosen destination for his escape was Canada, where the situation for academic freedom is terrible — and where they’re literally considering a law that would punish speech crimes with “imprisonment for life,” which is pretty…y’know…fascist.

While Stanley told the Times that he “respected FIRE’s recent principled defense of pro-Palestinian protesters” (i.e., “I’m glad they’re defending people on the left”), he also claimed that the “moral panic about leftism on universities is largely [FIRE’s] fault” (i.e., “I’m upset they somehow didn’t stop anyone with eyes from noticing how bad things got on campus the last ten years”).

This assertion was greeted with a bit of a chuckle by me, because just like podcaster Michael Hobbes (who has built his entire reputation on Cancel Culture not being real) Jason seems to be imbuing me (and Jonathan Haidt) with borderline omnipotence. Indeed, I’d have to have The Power Cosmic to be able to manufacture a situation on campus that anyone could see over the last decade had gone from bad to worse to disastrous.

And if I had The Power Cosmic, believe me: I’d be using it for something way more fun than this.

Like Hobbes, Stanley likes to reassure left-leaning America that there’s only one bad guy in the room, and that’s The Right — as if the right and the left don’t always exist in constant tension, often pushing each other to more extreme or ridiculous behavior. Haidt and I call this the “polarization spiral.” To not see this dynamic is to construct a child’s world of blameless good versus absolute evil, which is much too flattering to anyone at any point on the political spectrum.

But alas, a binary understanding of good and evil is often what passes for being intellectual these days.

Before we go on, here are some stats on campus Cancel Culture that are either totally normal examples of social consequences, according to Hobbes, or don’t really matter because the whole concern about campus speech is a moral panic FIRE largely engineered, according to Stanley:

One in six professors say they’ve either been punished for speech or threatened with punishment for speech. If extrapolated nationally, that would equal about 100,000 to 150,000 professors. There is no historical parallel where the number is as bad. None. (We even have a five-part series on ERI dedicated to expounding on this point, called “Cancel Culture is happening on a historic scale.” I urge you to check it out.)

Since the start of Cancel Culture in 2014, we’ve seen 1,200 professors targeted for punishment and over 200 professors fired. These numbers are about three times worse than the number of professors who were found to have been fired for being communists in the 1950s, and about twice the number of the professors terminated for political belief overall.

We get a lot of flack for that last figure because it just sounds too outrageous, but believe it or not, it’s actually a bad comparison in the wrong direction.

Prior to 1957, schools argued that they were getting rid of the communist professors because they were too doctrinaire and closed-minded, and therefore a threat to academic freedom. But this logic wouldn’t fly under Sweezy v. New Hampshire, a 1957 case in which the Court concluded that you can’t fire professors under academic freedom as protected by the First Amendment.

This is why it’s a bad comparison: Before Sweezy, it really wasn’t clear that it was even illegal to fire a professor for espousing wrongthink — and yet, we did it exponentially less often then than we do today.

Go figure.

In reality, you should only compare the modern situation to what has happened since the major cases protecting academic freedom and student free speech were handed down, which was between 1957 (Sweezy) and 1973 (Papish v. Board of Curators of the University of Missouri). When evaluating from 1973 onward, there is nothing that even vaguely compares to what we have seen on campus between 2014 and today — and that includes the chaos that followed 9/11.

As I’ve noted before, my career started by defending some pretty unpopular speakers in the wake of 9/11. At the time, there was a massive fear that we were seeing a major rolling back of free speech and academic freedom. I was part of that fight, so I definitely have the hate mail to show that I’ve been at this longer than practically anyone.

But do you know how many professors were actually fired during that time between 9/11 and the Iraq War? We know of three. And do you know what? Every single one of them was fired for a reason that didn’t in fact violate the First Amendment protections of academic freedom:

Sami Al-Arian remained fired because of his ties to terrorism.

Ward Churchill was fired not for free speech — a claim where FIRE spoke out on his behalf — but for gross academic misconduct.

And, in a case that I’ve explained before, Elizabeth Ito was fired because she spent 10 minutes of a 50-minute class on technical writing talking about her views on the Iraq War. FIRE was involved in that case, but I have since realized that, yeah, actually, a school can fire someone for doing something completely unrelated to their job for a substantial chunk of class.

So essentially, while several professors were punished for their speech in that period, none that we know of were fired.

This is why 200 fired professors between 2014 and today is infinitely more professors than were punished in the post 9/11 period — the worst crisis for academic freedom since 1973.

People like Michael Hobbes and Jason Stanley like to pretend things just aren’t that bad on campus. They’re wrong. As a group, campuses are economically unsustainable ideological monocultures that treat the public like a hostile foreign country. Defending our trillion-dollar-plus higher education industry is not revolutionary. It’s more like being a PR flak for America’s elite. Far from being brave rebels who speak truth to power, they function as self-interested apologists who speak a self-serving spin that locally gains them status from power.

What's worse, it's pretty clear that Jason Stanley actually knows that there was a problem on campus. The one time he actually spoke out against Cancel Culture was in 2022, in a tweet thread that Stanley later claimed was “poorly worded.”

That’s a strange thing to say, because the thread began with a pretty simply-worded “I have little patience for cancel culture."

That was a brief breath of fresh air, but unfortunately Stanley deleted his tweets once they caused an uproar. In an interview with Forward, he attempted to clarify:

So the stupid thing in my tweet, I put the cancel culture. I put some critique of cancel culture, but I didn’t really mean to attack cancel culture. I don’t even believe in cancel culture.

Yep. He had to backtrack, because attacking Cancel Culture while being a left-leaning professor at Yale really would be speaking truth to power.

It simply can’t be denied with a straight face that higher education has cultivated a monoculture in its faculty and administration. Those administrators and faculty use the Perfect Rhetorical Fortress to shut down critics and permit (sometimes encourage, sometimes participate in) illiberal student shutdowns of speakers and events. This culture polices anything it might perceive as the most infinitesimal micro-aggression — for example, avoiding phrases like “whipped into shape” because it evokes “imagery of slavery.” The exception to that rule is, apparently, when the aggression is against Jews, and then the administrators need context.

Higher-ed’s business model is also unsustainable; it spends more on administrators than teaching. In our study of 140 state schools, we saw administrator payroll eats 44% of every dollar spent, compared to 38% that goes to core educational functions like instruction or research.

Meanwhile, elite higher education has long insisted it needs the discretion to consider race in admissions and hiring in ways that were illegal since at least 2003’s Gratz v. Bollinger, if not 1978’s Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, while consistently using that discretion to admit more of the children of the top 1% income distribution than the bottom 60%. Also, the average student ends up about $40,000 in debt — and rest assured that the day after their graduation, the fundraising emails will start.

But for left-leaning professors like Jason Stanley, colleges have been awfully comfortable places. That is, until more recently, when their own ox is getting gored.

That is one of the reasons why we so deeply appreciate the Times article, which made it clear that it’s not at all commendable to defend the free speech rights of those you agree with. That’s just selfishness and self-interest.

If you don’t give a damn about when professors you disagree with are canceled, you’re not a fan of academic freedom or free speech at all. Hell, even the fascists were fans of academic freedom…for people who agreed with fascists! The Nazis only opposed “Jewish science” like relativity, after all.

As best I can tell, Stanley said almost nothing about the crisis while it was happening, and people like Hobbes made a career out of reassuring left-leaning audiences it was a hoax.

What it means to be a liberal, in the small-L liberal sense, is to believe in free speech even for people who hate your guts and say things you think are ugly and wrong. That’s the whole ball game. If you don’t hold that principle, you aren’t even playing.

And yes, for the record, I do believe in and will fight to defend the free speech rights of Jason Stanley and Michael Hobbes — not that Jason has many of those in Canada, sadly.

SHOT FOR THE ROAD

It was a pleasure talking with Coleman Hughes on his Conversations with Coleman podcast last week. We discussed The War on Words, my new book with free speech superhero Nadine Strossen; why I believe the cases against Rümeysa Öztürk and other visa holders on campus who faced deportation are weak; why President Trump can’t force Harvard to have more ideologically diverse professors (even if that would be good for the students); the real free speech crises in Europe; and many other topics.

Check it out here or wherever you get your podcasts!

This concept in particular needs more visibility in the broader culture. It's not only Stanley who doesn't make a distinction between fascism and right-wing authoritarianism, but almost the entire progressive left.

"fascism was a weird melding of left-wing and right-wing ideas, combining nationalism, racism, and socialism in a way that won more adherents than it ever should have — especially among intellectuals and, distressingly, on German campuses. Meanwhile, right-wing authoritarianism is basically the story of the human race prior to the 20th century, when left-wing authoritarianism started to become more prominent."

Totally on point, Greg. Regarding the Wolfson interview, that phenomenon has been absolutely driving me crazy: the denial that there's any sort of leftist indoctrination on college campuses, followed by words and actions that completely contradict that denial. The lack of self awareness is off the charts, and I've been meaning to write an article on it. It reminds of the quote (can't remember who it was) that says something like ideology is like breath, we don't notice our own.