Yes, the last 10 years really have been worse for free speech

My response to David Cole’s review of ‘Canceling’ in The New York Review of Books

ACLU National Legal Director David Cole has a review of my and Rikki Schlott’s book, “The Canceling of the American Mind,” coming out in the February 8 edition of the New York Review of Books. Overall I thought it was quite positive, but Cole made some arguments — which we actually hear quite often — that I think need addressing.

Before I do that, though, I want to stress that I both like and greatly respect David Cole. I also appreciate that the New York Review of Books found such a serious thinker on the topic of freedom of speech to review our book, as opposed to the many First Amendment skeptics these days who seem to think that simply employing a more advanced insult technology against those they disagree with is the same as refuting them (cough, cough — “The Lost Cause of Free Speech”).

I always welcome good-faith pushback — especially when it gives me an opportunity to go into more depth on why Rikki and I are so concerned about the current situation in higher education. All that said, here are some quotes from Cole’s review that I’d like to respond to:

‘[Lukianoff and Schlott] assert, for example, that the past decade has seen repression of speech akin to or worse than that of the McCarthy era.’

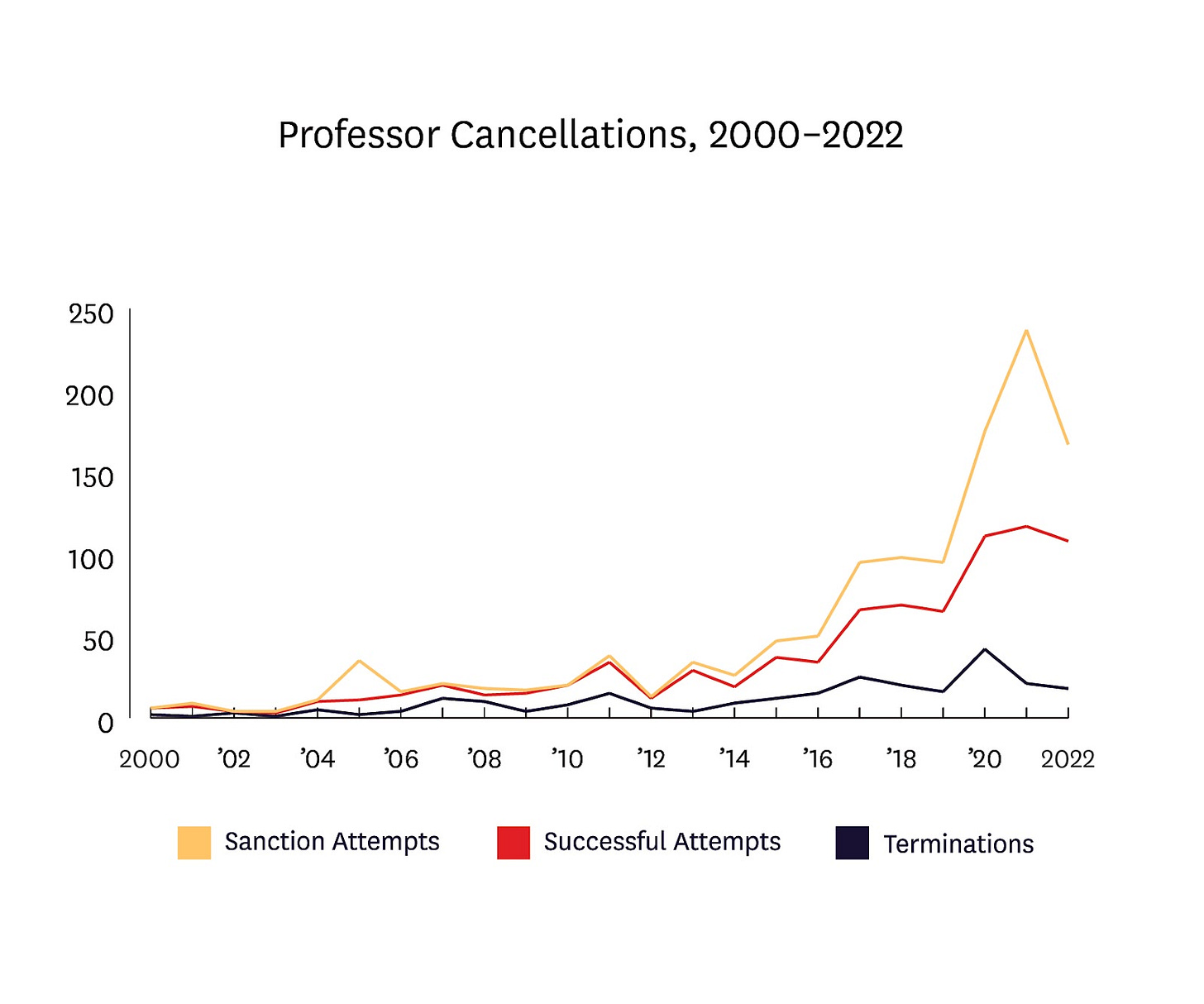

This makes it sound like we actually wrote, “Cancel Culture is worse than McCarthysim!” when we actually wrote something much more specific. We didn’t use the word “McCarthyism” in the book, but we did refer to that particular period of censorship as the Red Scare. Still, we only referenced that three times in the entire book. Once was to say that we believe people will study Cancel Culture the same way we study the Alien and Sedition Acts or the Red Scares (there were two). Another time was to point out that the Hollywood Red Scare only targeted about 300 people, in order to give people the sense of the comparative scale of Cancel Culture. In the third, we pointed out that there have been more professors fired during Cancel Culture than were fired during the Red Scare — which is simply true.

In fact, we refer in the book to 100-150 professors fired in the 11 years of the second Red Scare, and we compare that to the almost 200 that have been fired in the nine-and-a-half years of Cancel Culture (2014 - 2023). However, I realized later that counting 150 for the Red Scare was wrong, because that extra 50 was apparently just tacked on by people assuming the 100 estimate from the largest study done in the ‘50s must be larger. I am confident that more than 100 professors were fired, but you need to compare what the estimate was at the time of the second Red Scare with what the estimate is now, while Cancel Culture is actually occurring. Doubtlessly, additional people will come forward over time, and I believe that the same thing will happen for Cancel Culture — and probably on an even larger scale once people become less worried about the NDAs they had to sign. Regardless, comparing 100 fired professors then to nearly 200 now, with about a year and a half’s difference in favor of the second Red Scare, still makes my point.

Most importantly, whenever I’ve talked about Cancel Culture since, I’ve been pretty clear that I’m talking about on campus, not the country as a whole. The numbers on campus are alarming, and the statements Rikki and I make bear that out. For example, as my colleague Adam Goldstein and I detailed in a piece for Fox News, 1 in 10 students surveyed for FIRE report that they've been either threatened with punishment and investigation or actually have been punished or investigated for their speech. Extrapolated out to the entire population on campus, that amounts to more than one million students nationwide. And a 2022 survey of college faculty showed that 1 in 6 reported having either been threatened with punishment or investigated for their academic freedom or free speech, which equals tens of thousands of professors. There is no evidence that the Red Scare threatened professors and students with official sanction on anything like that scale.

And keep in mind that prior to the case law decided after the Red Scare, from 1957 to 1973, it wasn’t even clear that the First Amendment prevented public colleges from firing professors or expelling students for speech or beliefs. We make this point repeatedly in the book because professors and students are now supposed to be protected by the First Amendment, and yet we still see investigations and firings on an unprecedented scale.

As I note in a piece for The Atlantic, which I encourage you to read if you haven’t already: “In the late 1950s, when McCarthyism ended, only 9 percent of social scientists said they had toned down anything they had written because they were worried it might cause controversy.” By comparison, I point out:

Last year’s FIRE survey found that 59 percent of professors are at least “somewhat likely” to self-censor in academic publications. With respect to publications, talks, interviews, or lectures directed to a general audience, that figure was 79 percent. And the problem continues to get worse: 38 percent of faculty said they were more likely to self-censor at the end of 2022 than they were in September 2020. A 2021 report by the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology found that a staggering 70 percent of right-leaning academics in the social sciences and humanities self-censor in their teaching or research.

Even worse, in that CSPI study, more than 90% of faculty said they are likely to self-censor their beliefs in the future.

Then, of course, there’s the Conformity Gauntlet, which we discuss in “Canceling” but which Rikki and I recently updated with even newer data for Reason Magazine. In that piece, we show how a high school student graduating today who hoped to be a professor would face political litmus tests at every stage of his education — including when applying to conferences — if he survived all of those hurdles and became a professor. He’d also face bias-related incident programs that encourage students to report their fellow students and professors (sometimes anonymously) for allegedly offensive speech. He’d also have to be admitted to college, then graduate school, and get a job as professor despite the fact that a substantial portion of those tasked to admit him openly state they would discriminate in hiring against candidates they view as conservative.

We point out layer upon layer of conformity-inducing pressure on top of that, culminating in the final insult: Even if he were to survive all this and complete some groundbreaking research, major publications, including Nature Human Behavior, might not see fit to publish him if they can argue his findings are in any way “harmful to groups.”

FIRE has been around for 25 years this year, and I have been with the organization for 23 of those years. Bias-related Response Teams, DEI-informed political litmus tests, a large-scale speech policing bureaucracy, and ideological purity statements at major scientific journals simply did not exist until recently. Things have clearly taken a downturn, which leads me to the next point Cole makes that I want to address:

‘Lukianoff and Schlott’s contention that cancel culture began in 2013 and is worse today than ever before also seems questionable.’

We certainly don’t say the climate for speech is worse than “ever before.” The situation for free speech was absolutely worse prior to the First Amendment being strictly interpreted between the 1950s and the 1980s — which is why we consistently add “since the law was established” whenever we compare the current situation to the past.

Our book is also filled with data and examples that show that something really did change since 2014, not subtly, but dramatically — making the current moment worse than any that we could find in the last 50 years since the law was fully established on campus.

To clarify, here is our definition of Cancel Culture:

The uptick beginning around 2014, and accelerating in 2017 and after, of campaigns to get people fired, disinvited, deplatformed, or otherwise punished for speech that is — or would be — protected by First Amendment standards and the climate of fear and conformity that has resulted from this uptick.

As we further explain, Cancel Culture as we define it required the first generation who grew up with social media and smartphones in their pockets to hit college, which only happened around 2014. And as we’ve mentioned many times at this point, we are arguing that Cancel Culture should be thought of as a particular historical period, not just a general, all-purpose term for any kind of censorship or ostracism. A lot of times the argument, “But Cancel Culture goes way back!” is really just another way of saying that censorship, exclusion, and closed-mindedness are ancient. Of course they are. But the ability and inclination to start Twitter mobs to get people flash-fired, which is a defining characteristic of Cancel Culture, is pretty dang new.

Then, of course, there’s all the data that shows things truly have gotten worse.

As I mentioned in The Atlantic article, after 9/11 only about three professors lost their jobs for speech related to the attacks or the subsequent wars, and all three were fired for reasons that extended well beyond protected speech. Meanwhile, since the dawn of Cancel Culture in 2014 there have been more than 1,000 professor cancelation attempts, with two-thirds resulting in some form of sanction and one-fifth resulting in termination:

Also, here we should address an assertion made not by Cole, but in the subtitle of the review:

“Conservatives often charge their opponents with ‘cancel culture,’ but the right poses as significant a threat to free speech as the left.”

Not quite. We found that about one-third of the punishments faced by professors initially start on the right — oftentimes in conservative media— but even those firings or punishments are almost always carried out by administrators who are themselves on the left, given that at most schools the administrative class is overwhelmingly, usually more than a super-majority, left-leaning.

This was an argument I made in an Intelligence Squared debate many years ago: If the left were still as good on free-speech as it was in the past, none of this massive censorship would be possible, no matter what political direction it comes from, because the overwhelmingly left-leaning administrators wouldn't humor the attempts, let alone carry the cancellations out.

Given the ideological bent of campus administrators, the major censorship threats from the right actually come from Republican legislatures. However, as we'll see below, sometimes people have the impression that the clearly unconstitutional threats in higher education, for example, are far more common than they actually are (to repeat, there has only been one clearly unconstitutional law targeting curricular speech directed at higher education: the “Stop WOKE Act” — which, as of now, FIRE has defeated).

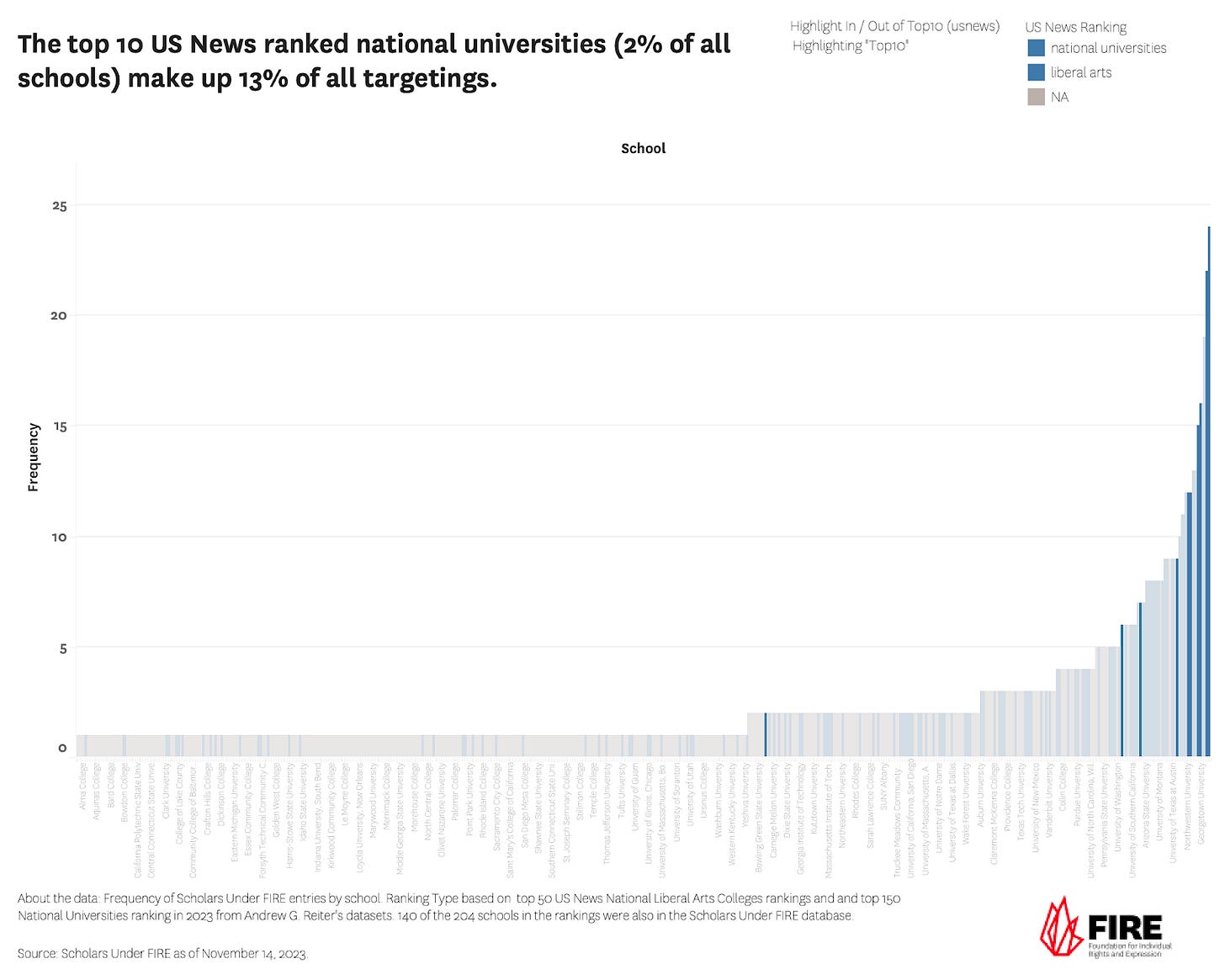

And the level of Cancel Culture in higher ed is all the more remarkable given how little viewpoint diversity already exists across the board (many departments have virtually none). As I’ve joked many times, it’s remarkable that they’re still finding witches to burn:

Also, keep in mind that this is all wildly concentrated among the most elite colleges in the country, with the U.S. News & World Report’s top 10 colleges accounting for a hugely disproportionate share of cancellations and cancellation attempts:

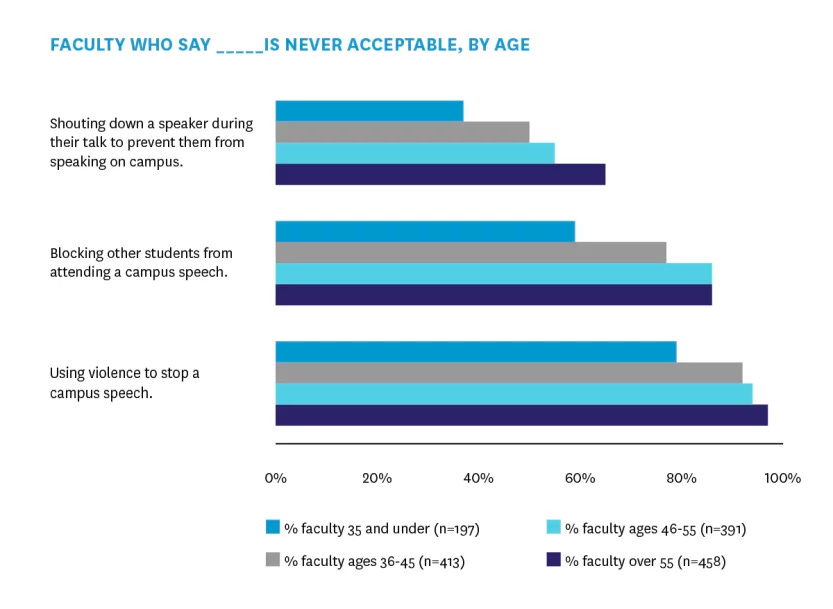

It’s also important to note that the problem will only get worse as older faculty, who are generally far better on free speech, begin to retire in large numbers. In our 2022 survey of faculty, we saw that the younger the faculty were, the more acceptable they found anti-speech activity:

What about students, though? Using data from UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute, Jean Twenge has shown that support for censoring extreme speakers on campus has spiked in recent years: “While only 1 out of 4 students wanted to ban extreme speakers during the 1970s and 1980s, the majority wanted to do so in 2019.”

What’s more, Nate Silver, looking at our 2024 College Free Speech Rankings survey data, saw how little support there was for speech among students, noting that:

“[a] significant minority of students don’t even have much tolerance for controversial speech on positions they presumably agree with… this looks like a major generational shift from when college campuses were hotbeds of advocacy for free speech, particularly on the left.”

We’re seeing this speech intolerance start to impact the country as a whole, too. A 2023 Pew survey found that a majority of Americans — 55%, up from 38% in 2018 — support government efforts to restrict false information online, even if it restrains free speech (and that’s without considering who gets to decide what’s false — something government’s historically aren’t, to understate, great at doing):

Regarding the assertion that ‘many other states have passed similar laws’ to Florida’s Stop WOKE Act

Well, no, that’s not actually true. The Stop WOKE Act was the only state statute enacted that directly affected classroom instruction in higher ed in an unconstitutional way. This can be easy to miss in the media coverage of these laws, but it really was the only one applied to higher ed and the only one that impacted classroom instruction. And as I mentioned earlier, it’s also been defeated so far (it's on appeal) by both FIRE and the ACLU.

In the meantime, that leaves the California Community College DEI policy as the most clearly unconstitutional policy not yet enjoined in the country (though a magistrate judge has already said it should be enjoined as unconstitutional) — but that gets very, very little media coverage even though it does something that’s arguably worse: Compelling professors to promote ideas they may not agree with. These include acknowledging that “cultural and social identities are diverse, fluid, and intersectional,” and developing “knowledge of the intersectionality of social identities and the multiple axes of oppression that people from different racial, ethnic, and other minoritized groups face.”

In his review of “Canceling,” Cole goes on to mention the “Don’t Say Gay” bill in Florida — which we also criticize in the book — as a comparable act from the political Right. This comparison doesn’t work, however, because the “Don’t Say Gay” bill deals specifically with K-12 curriculum. The state generally has — and, I believe, should have — some say in what public schools (which are mandatory, taxpayer funded, and educate our children) teach. While Cole, as well as Rikki and I, have every reason to be critical of many of these laws applied to the K-12 curriculum, legally speaking, they are quite distinct from the very clear speech-protective laws regarding higher education.

There has also been, not by Cole but by others, some conflation of the laws that require universities to cut down on their DEI bureaucracy. To the extent that those limit the rights of professors and students, FIRE adamantly opposes them — but some of these laws are quite clearly directed only at the bureaucracy itself. And every time that gets mentioned, free speech defenders should note that DEI administrators and bureaucracies have been threats to free speech, academic freedom, and the marketplace of ideas on many many campuses, as I wrote last week.

‘Lukianoff and Schlott do not acknowledge it, but in recent years universities and colleges have in fact undertaken substantial efforts to promote free speech on campus (no doubt in part because of FIRE’s and others’ persistent advocacy).’

Guilty as charged here — and I think this may be just a difference of opinion between me and David Cole. We at FIRE have defeated scores of speech codes and saved countless professors and students from punishments for their clearly protected speech, but that doesn’t mean we don’t still have a major free speech problem on campus. When it comes to tuition costs, bureaucracy, and viewpoint diversity — before you even get to the major threats to academic freedom and free speech — higher ed is in bad shape and needs major reform.

The beginning of a solution is not the same thing as the end of a problem. We have seen proposals to help with the free speech environments on campuses come and go (and go, and go) over the years. As we saw in the late ‘90s and ‘00s, defeated speech codes often come back. Sometimes they are verbatim to ones that were defeated in court. Schools that have changed policies to respect civil rights when donors are mad also tend to backslide as soon as students are angry enough at a professor’s or fellow student’s speech. Administrators who champion free expression retire and are replaced by administrators with other concerns. Many well-intentioned programs aimed at solving the problem also have no effect on the campus climate at all.

I am aware of some of the programs Cole references, and I do hold out some small hope for them. But as long as schools maintain DEI requirements in their admissions and hiring essays, maintain “bias related incident” teams, flirt with or straight up employ restrictive speech codes on campus, have literally no viewpoint diversity in many departments, and remain places where so many students and faculty are afraid of saying what they really think and being investigated for their speech, we are nowhere near the finish line.

As I’ve said before, my big fear is that a lot of these efforts that schools are taking on are simply window dressing — attempts to make themselves look just good enough so donors will keep giving to them and students will keep going into tremendous debt to enroll. If we’re really going to turn things around, I think we need big, big changes — and a lot of help.

Special thanks to: Adam Goldstein, Nate Honeycutt, Talia Barnes, Angel Eduardo, Sean Stevens, Komi Frey, and Perry Fein for their help putting this beast together! Adam, by the way, is ALSO the creative talent behind ERI’s great Midjourney art!

SHOT FOR THE ROAD

I was thrilled to be invited to talk to the very funny Adam Carolla, on the not-so-creatively-named “Adam Carolla Show” podcast. Carolla is an old free speech ally who we were lucky enough to include in our 2015 documentary on the intersection between Cancel Culture and comedy, “Can We Take a Joke?” (This film was so ahead of its time that “Cancel Culture” was not even a popular term yet. Instead we called it “outrage culture.”)

"In the meantime, that leaves the California Community College DEI policy as the most clearly unconstitutional law on the books in the country — but that gets very, very little media coverage even though it does something that’s arguably worse: compelling professors to promote ideas they may not agree with."

But why? Why does this problem with the California Community College (CCC) system receive so little attention? I saw Bill Maher interview CA governor Newsom last week, and I was hoping that Maher would ask about this genuinely troubling issue in Newsom's state. Instead, Maher conducted a disappointingly softball interview. He even allowed Newsom to dismiss DEI criticism as a right-wing phenomenon without pushing back on that mischaracterization at all.

And I can think of only three relatively high-profile centrist/Liberal types who have written on the DEI censorship at CCC: Conor Friedersdorf at The Atlantic; David French at the NYT; and Mr. Lukianoff on Substack, at FIRE, or in his books. Where is everybody else?

Brilliant response. I am glad that Substack gives writers a means to respond to book reviews.