These free speech sayings are falling out of favor. What does that mean for our culture?

A world where “Words are violence” is more common than “Sticks and stones…” is a world oriented against free speech principles. But we can turn that around.

When’s the last time you heard someone say, “To each their own”?

What about “It’s a free country,” “Who am I to judge?” or “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me”?

How often do you use these sayings in regular conversation these days?

If your answer is “Not very often,” you’re in pretty good company. While working on The Canceling of the American Mind with the Gen-Z journalist Rikki Schlott, Greg learned not just that a culture’s values are conveyed in common sayings and idioms like these, but also that his young co-author barely heard them growing up.

This was concerning, so FIRE decided to look into it*.

In May, we surveyed 1,122 American adults about common expressions related to free speech and intellectual pluralism. And while the results show some promising potential trends, they also illustrate ways our cultural climate isn’t as free speech-friendly as it could be.

Survey says: Most people know of the idioms, but don’t often hear or use them

Before we go further, a quick pedantic point: It can be argued that many of the sayings in question aren’t technically idioms, which are defined as common phrases or expressions that carry symbolic rather than literal meanings — e.g., “raining cats and dogs,” “break the ice,” or “by the skin of my teeth.” And while we love being pedantic, let’s agree to use a looser definition of the term, which can be interchangeable with “expression,” “phrase,” or “saying,” for the sake of this piece.

The FIRE/NORC 2025 Idioms Survey, which was conducted through NORC’s AmeriSpeak panel, focused mainly on participants’ familiarity with and usage of the following expressions:

“Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.”

“It’s a free country.”

“Everyone’s entitled to their own opinion.”

“Walk a mile in someone else’s shoes.”

“To each their own.”

“Different strokes for different folks.”

“Who am I to judge?”

“Address the argument, not the person.”

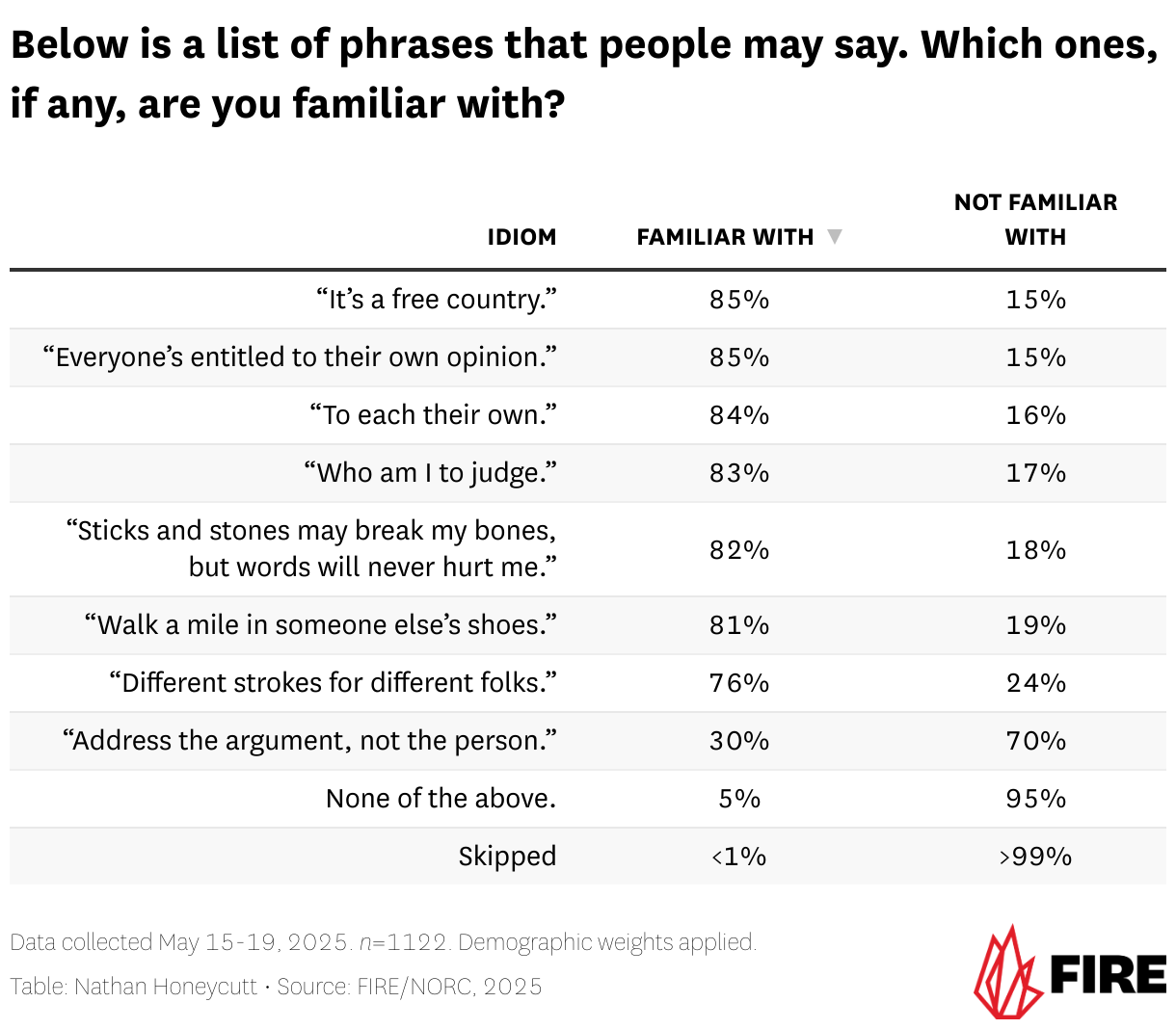

The good news is, recognition of the vast majority of these idioms was generally very high across all participants, ranging from 76 to 85%.

In fact, only 6% of surveyed participants said they hadn’t heard any of these expressions before.

Given that these particular sayings tend to communicate perspectives that are in favor of “small-D” democratic values like free speech, epistemic humility, and intellectual pluralism, it’s a very good thing that people are familiar with them.

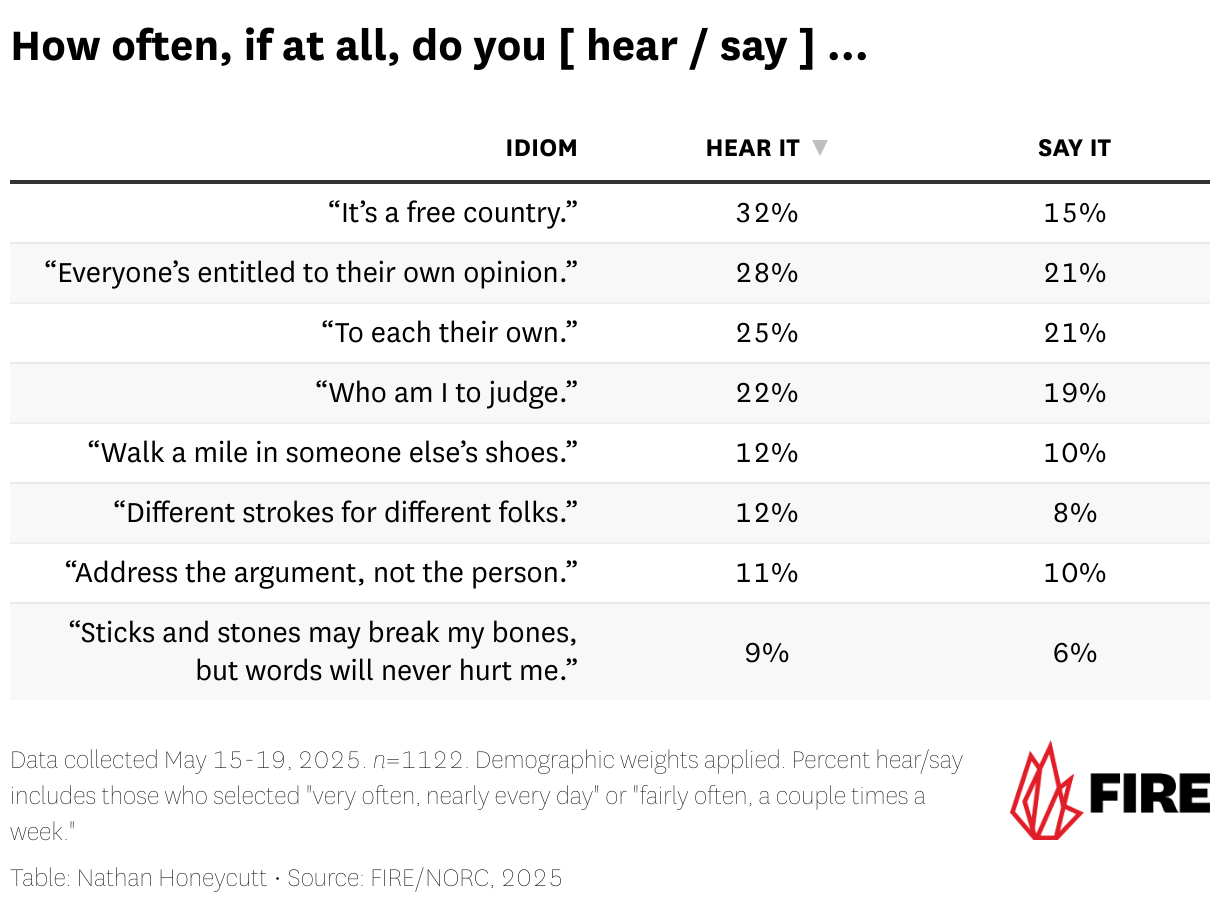

The bad news is that, while recognition was high across the board, participants reported both hearing and using these phrases at low numbers.

For each of the selected idioms, 30% of participants or fewer said they heard them used “fairly” or “very” often, and at most only 21% reported using them “fairly” or “very” often themselves.

Even the most well-known phrases still achieved low double-digit results on the survey questions. For example, there are few sayings that would be more helpful for the promotion of free speech culture than “Everyone’s entitled to their own opinion,” and we’d love for it to be more prevalent in our culture. Unfortunately, only 28% of participants reported hearing this expression either “fairly” or “very” often, and only 21% reported using it at those same levels.

If you’re like us, you’re often confused by or skeptical of statistics like these because of how they can be misused or misinterpreted. So let’s frame them in the inverse for clarity:

Seventy percent of participants said they hear these idioms used “occasionally, a handful of times,” “rarely, once or twice,” or “never.” Seventy-five percent of participants said they use them at those same levels.

That’s a pretty large majority whose engagement with those expressions is slim to none.

It’s also important to note here that while the sample size for this survey (1,122 Americans) may seem small, nearly all research of this kind uses similar numbers of participants. In fact, as long as they are appropriately randomized and representative — which surveys fielded by NORC always are — sample sizes like these tend to have a very low margin of error.

All of this is why it’s fair to say that based on our survey results, these phrases are not heard or used nearly as much as they should be.

‘I can’t get to sleep. I think about the implications…’

Now, you may be wondering, “Okay, so these idioms aren’t used much anymore. So what?”

Well, as British Council Academic Director Amy Lightfoot and Head of Research Mina Patel recently wrote:

Idioms often go beyond their literal meanings, acting as linguistic time capsules that preserve the values, norms, and global influences of the past… They shape how we relate to one another, communicate shared values, and mark ourselves as part of a group, whether that group is a generation or a nation.

Given that, what does it say about our culture that the phrases in question seem to be growing less common? What sorts of expressions have arisen to take their place — and what do they say about how we relate to one another, what we think, and what we care about?

As Greg and Jonathan Haidt wrote in The Coddling of the American Mind, the norm throughout human history has been “honor culture,” which consisted of using violence to defend one’s property and social standing against threats. Think of someone challenging an opponent to a duel over an insult. As anyone familiar with Alexander Hamilton will know, this was pretty high-stakes stuff.

More recently in our history, however, democratic societies began to replace honor culture with “dignity culture” — in which there is a bright distinction between words and violence, and a taboo against crossing that line. Think of the quote often attributed to Sigmund Freud, “The man who first flung a word of abuse at his enemy instead of a spear was the founder of civilization.”

The idioms we surveyed about are the kind that emanate from, promote, and preserve a dignity culture. The fact that they’ve become less common signals a shift to something else — what Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning call “victimhood culture.”

In their book The Rise of Victimhood Culture: Microaggressions, Safe Spaces, and the New Culture Wars, Campbell and Manning show how our society has blurred the distinction between words and violence, changing the way we interact with ourselves, each other, and with governmental authority. As a result, dignity culture idioms have fallen by the wayside and have been replaced with expressions reflecting victimhood culture norms.

Consider “Sticks and stones…” which scored the lowest in the FIRE/NORC survey in terms of how often they were heard and used (9% and 6%, respectively). Sure, this is an old grade school rhyme, and maybe part of its diminished prevalence has to do with the fact that we only surveyed adults. But there is also evidence that there could be more to it.

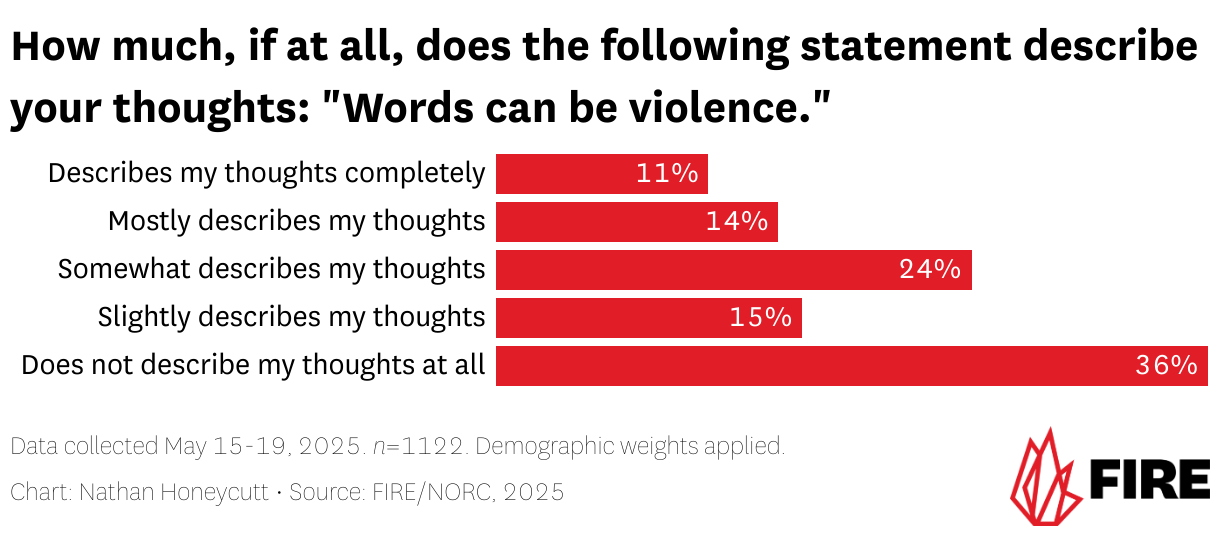

Both Greg and Jonathan Haidt have written before that the philosophical and rhetorical inverse of the “Sticks and stones” idiom, “Words are violence,” has become more and more well-subscribed to in the last decade or more. In fact, the same FIRE/NORC survey included a question about that.

When asked how much “Words can be violence” describes participants’ thoughts, 11% said it describes them “completely,” and 14% said it “mostly” does so. Twenty-four percent said it describes their thoughts “somewhat,” and 15% answered “slightly.”

Only 36% of participants said that “Words can be violence” does not describe their thoughts “at all.”

Again, reframed for clarity, this means 65% of participants considered “Words can be violence” to at least “slightly” describe their views. Combine that with the 32% of college students in FIRE’s 2025 College Free Speech Rankings who believe using violence to stop disfavored speech is at least “rarely” acceptable, and you have a real issue on your hands.

It’s important to note here, as Angel has argued before, that there are many cases and contexts in which even “rarely” is rightly considered too often: Plane crashes. Not paying your taxes. Selling government secrets to foreign agents. All of these, even if they happen rarely, we have good reason to treat as unacceptable and work to minimize.

It should be obvious, then, why blurring the line between speech and violence falls under that category too. Sadly, it isn’t obvious to many people at all.

Why ‘Words are violence’ signals a terrible shift in our culture

This topic is one we frequent on ERI, but it unfortunately bears repeating — and repeating, and repeating.

In fact, Greg’s newest book, co-written with FIRE Senior Fellow and former ACLU president Nadine Strossen, The War On Words: 10 Arguments Against Free Speech–And Why They Fail (available now wherever you buy your books!), dedicates a chapter to this seemingly immortal canard.

At the risk of boring those of you who, like us, think this is a no-brainer, we’ll cover it again briefly here.

If sticks and stones may break your bones but words can never hurt you, you are invoking a spirit of resilience toward criticism, scorn, and general dissent. A consequence of that resilience is an acknowledgement of the difference between words — even harsh ones — and violence. This will naturally lead you to recognize the critical importance of free speech, open discourse, and free inquiry in our culture.

In that frame of mind, free expression becomes, as Greg put it in his recent TED Talk, the cure for violence.

But if you believe words are violence, you are cultivating a culture of intellectual and emotional fragility, which will inevitably lead to a whole host of mental health consequences. Moreover, criticism, scorn, and dissent become existential crises and imminent dangers to your well-being — which means censorship becomes a matter of personal safety.

And, of course, because the line between them is now blurred, violence also becomes an acceptable response to disfavored speech. One need only to look at the unrest on college campuses over the last two years for the results of that line of thinking.

These are mutually, philosophically incompatible idioms. If one of them is all over academia, politics, and popular culture, it must mean the other is largely absent from those same arenas.

Why does this matter? Because the principles we hear, learn, and promote influence how we think and what we believe. This, in turn, drives our behavior. Our behavior, then, affects everything and everyone around us.

The prevalence of “Words are violence” and the relative scarcity of “Sticks and stones…” spells trouble for “small-L” liberalism. It perpetuates the “tell an adult” method of conflict resolution far beyond elementary school and long into adulthood, which is both intellectually and morally stunting. Also, by appealing to authorities to handle disagreements arising from violations of victimhood culture, we are basically guaranteeing the abuse of that authority. This, in turn, threatens our civil liberties — not to mention our capacity for individual and cultural growth.

We need a groundswell of action to reverse the trends of victimhood culture. Thankfully, there is a way forward.

‘If there is hope, it lies in the polls’

Despite the concerning trends we’ve outlined here, there is also some cause for optimism. First, if our survey results indicate that overall recognition of these idioms remains fairly high, we’re spared the difficult task of having to reintroduce them. It’s always heartening to know that we aren’t alone, and that we don’t have to start from zero in our efforts.

Second, while recognition of these phrases is slightly lower among surveyed younger Americans (possibly due to the fact that older people have had more time to hear them), they also reported slightly higher usage of a few — including “To each their own” and “Who am I to judge?” Also, despite the fact that those who recognized these idioms skewed older, there was a larger proportion of young Americans who said they hear most of these phrases “fairly” or “very” often. In some cases, they did so by double-digit margins over their elders.

That’s good news, isn’t it? Is the tide turning on the Age of Cancel Culture? Are the youth rediscovering the principles undergirding many of these expressions? The numbers are too small to go that far — but it’s certainly a potentially encouraging sign.

It’s also something each of us can help with, right now, in our daily lives: We have to find ways to reemphasize these idioms, to argue for the values and principles they are meant to communicate, and to bring them back into common usage by using them ourselves.

Defending the eternally radical idea of free speech against the impulses, intuitions, and intentions of actual and would-be censors is often exhausting work. It can be tough to summon the energy to keep going, and it can be very easy to feel like you’re just punching the ocean. But we’re always invigorated by the realization that there’s actually a lot that we, as individuals, can do to fight the good fight.

So let’s bring these idioms back. Let’s use them more frequently. Let’s see if we can’t get our younger generations to become more familiar with them through our example. If we try to espouse and embody the dignity culture values of resilience, free inquiry, and intellectual humility, maybe the next generation will grow up not just knowing these idioms, and not just using them, but also knowing why they should.

And if you disagree, that’s fine. After all, everyone's entitled to their own opinion!

*Special shout-out to FIRE Research Fellow Nate Honeycutt for his great work on the FIRE/NORC survey, and for assisting us with the data here!

SHOT FOR THE ROAD

On Monday at 4pm Eastern, FIRE will be hosting a special webinar (in collaboration with ERI & So to Speak) featuring a conversation between former President of Harvard and former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers and me (moderated by Nico Perrino) on the latest developments in the Trump administration’s war against Harvard. Hope you can join us!

“…these particular sayings tend to communicate perspectives that are in favor of “small-D” democratic values like free speech, epistemic humility, and intellectual pluralism…”

More accurately, they are in favour of “small-L” libertarian/classical liberal values. Democracy, whether real or the normal oligarchic pretence, is a danger to them.

https://jclester.substack.com/p/democracy-a-libertarian-viewpoint

Also, “It’s not my cup of tea.” Wokies take offense when a person indicates lgbtq, political activism, collectivism, racial grievance, “social justice,” etc. just “aren’t my thing.” Seriously, some of us enjoy simple conversations about music, movies or baseball. Call us old fashioned.