My TED Talk is out today!

Here’s how I got into that famous red circle.

I’m proud to announce that my first-ever TED Talk is released today!

I hope you’ll give it a watch.

In the spirit of transparency (and maybe a little catharsis), I want to share how I actually ended up in that famous red circle and what it took to get there. While I was only onstage for 12 minutes, it was actually many, many months in the making. In fact, the story begins back in January.

I was contacted early this year by my old friend Claire Lehmann of Quillette to see if I’d be interested in giving a TED Talk. And, at the risk of offending some of my new friends at TED, I was… ambivalent. While I’ve enjoyed many TED Talks over the years, I’ve also found some of them to be overly formulaic. If I was to do one, I’d want to make sure I could avoid it turning out that way.

I was also turned off by the whole Coleman Hughes debacle back in 2023. This is something my team and I feel needs more explanation elsewhere, but it basically boils down to this: A vocal minority within TED had outsized ideological and curative power over the programming, which led to Hughes’ talk — about the merits of colorblindness — being intentionally under-promoted and as a result relatively unseen. In short, that was not cool.

However, I came to learn that TED’s new model of involving guest curators like Claire is at least partly designed to improve viewpoint diversity. That was definitely made clear to me once I arrived at the conference in April. I found myself among thoughtful people like my old friend (and FIRE Advisory Council member) John McWhorter and my new friend Liv Boeree. That was a good sign, and I certainly ended up feeling glad I’d done it.

But there was another reason for my hesitation to sign on: I suspected it would be an enormous time commitment. Having watched a number of TED Talks — often given by people I knew personally — I was amazed that they weren’t using notes or teleprompters. They performed as if they had rehearsed their talks a hundred times. Many of them probably did exactly that. I know I did. Without a doubt, this was the most demanding speaking project I’ve taken on in nearly 24 years of doing this work.

The TED conference was to happen four months from when I was invited. That might seem like plenty of time, but it goes by way more quickly than you expect. And given how insanely busy we at FIRE are, four months doesn’t seem like very much time at all.

Still, this was an incredible opportunity to put FIRE — and free speech, more broadly — on an important stage at a very important time. I couldn’t pass it up.

So if you’ve ever dreamed of standing in that red circle, or you’re just curious about what goes into one of these things, here’s how it went for me.

The process is process

I have to give a huge thank you to Bob Ewing and his entire team at The Ewing School, which has worked with FIRE for years to strengthen our team’s public speaking. That includes his wife Maryrose, and also Kim Hemsley, one of their fabulous coaches. These wonderful people helped with everything: brainstorming, script editing, and ultimately, delivery — which, unsurprisingly, was the most painful part.

Our collaboration with The Ewing School over the years has been incredibly beneficial, especially for me. You might not guess it, since I give so many talks, but I hate public speaking. I truly, deeply hate it. Jerry Seinfeld was right on the money when he joked that at a funeral, the average person would rather be in the casket than doing the eulogy. Sure, I have fun sometimes, but overall the experience is exhausting. I usually want to sleep for 11 hours — or crawl into a cave — when it’s over.

But despite my public speaking experience, prepping for this TED Talk was even more nerve-racking. I’ve never fully memorized a talk before. Bullet points? Sure. But I’ve always had notes to refer to. This time, I couldn’t do that — and I couldn’t just wing it, either. TED wants (and deserves) precision.

Now, the very kind people at TED will tell you they don’t expect you to memorize your talk. But what they really mean is, they want you to know it so well, inside and out, that you can do it in your sleep and riff on it while you’re up there. In other words, have it be internalized down to the word, but make it look spontaneous.

In other words, “Don't just learn to play Bohemian Rhapsody, but know it well enough to be able to do an acapella/jazz riff on it that looks impromptu.”

No pressure!

The initial plan was to do a talk on higher education reform. I spent an intense weekend trying to cram a meaningful, story-rich talk into something that could be done in about 10 minutes. It quickly became clear that this was a fool’s errand. There was no way to do it without making the whole thing shallow.

So I abandoned my initial plans and proposed something more timeless. This seemed amenable to the TED folks, but they reminded me to include lots of stories and avoid getting too theoretical.

So with that, I got to work.

Drafting, rehearsing, rewriting, rehearsing, and more

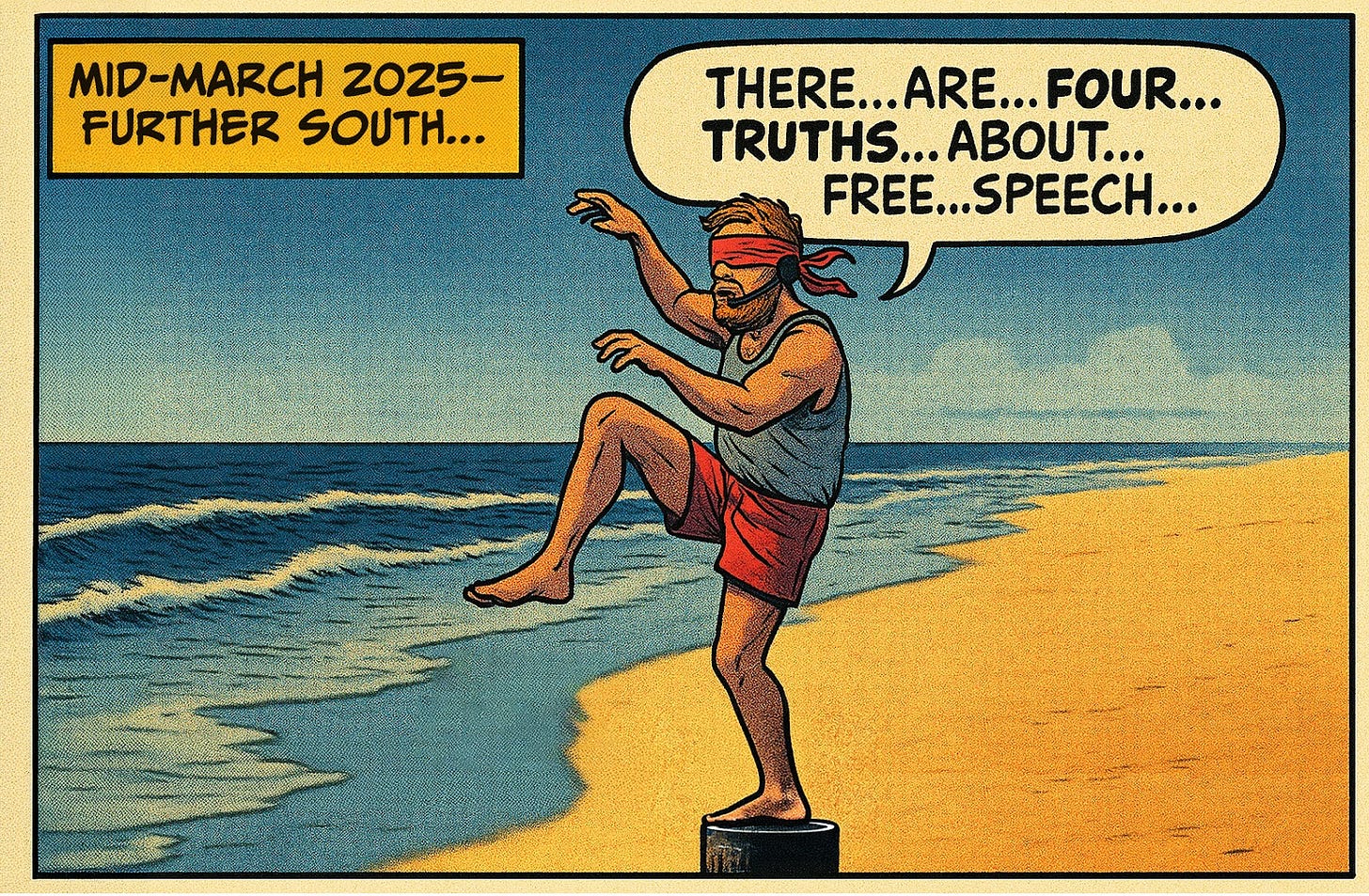

My first draft focused on addressing four big myths about free speech:

Words can be a form of violence.

Free speech is a tool of the powerful.

There's no value in anything dubbed “misinformation.”

Bad people only have bad ideas.

I was actually pretty proud of it, and I thought I was coming along really well. That is, until I began workshopping it with Bob and Maryrose. TED emphasizes storytelling, and often recommends hinging your talk on one central narrative. But I wanted ideas. I wanted to cram as much as I could into a 12-minute window (okay, it’s officially 10, but there was some wiggle room).

As a result, the talk gradually shifted away from the negatively-framed “Don’t do this” approach Jonathan Haidt and I used in our book “The Coddling of the American Mind,” and toward a more positive message — focusing on what is true rather than what isn’t.

Also, because I dictate almost everything, I figured my draft would already sound like a talk from the jump. I mean, it literally was me talking already. That should translate, right?

Wrong. It was a mess, and every aspect of my script needed a lot of work. It turns out that giving a talk is much more than just talking. Who could have known?

Anyway, I kept refining it. And refining it. And refining it. In fact, I was still making changes two days before the actual conference — shortening sentences, cutting asides, doing my best to streamline and perfect what I wanted to say so it would have the maximum impact.

I submitted my first script in early February, then spent weeks training on it with Bob.

Once it reached a certain level, I recorded it and started listening to it on repeat while working out. In retrospect, I started this step too early. My opening was initially radically different from my final version, and because I had drilled it into my mind that way I kept reverting back to it in later rehearsals.

We held an initial run-through in New York a few months before the real thing, with some people from TED — including TED’s leader Chris Anderson and head of media and curation Helen Walters — in attendance. My performance was…not great. I assumed there would be a printed copy of my talk there for me to work with, but there wasn’t, which put me off my game already. I ended up flatly delivering my talk like a nervous fifth-grader giving a book report on The Pilgrim’s Progress. To top it off, I admitted to the room beforehand that I despise public speaking, which is probably not the best thing to say to a group of people whose literal job is public speaking.

To my surprise, though, the feedback was not “You, sir, just suck!” It was extremely positive and constructive. Chris’ advice was especially helpful to me. He pointed out that audiences need a bit of “throat-clearing” about free speech up front. Otherwise, they might resist the message. He also warned against overly precise data points — because once you say “68.7%,” people stop listening and start silently fact-checking.

So it was going better than I expected, but I still needed a lot of work, and a lot more help.

Enter Kim: The perfect presentation coach

Kim is an expert on stagecraft, presence, and delivery. She’s an absolutely lovely Brit, and we bonded over our mutual UK connections (my mother is British). She learned quickly not to tell me to “have fun” because, like being told to “be happy” or “be present,” that just guarantees I’ll do the opposite.

Kim taught me so much throughout our time working together. Most memorably: if each point flows logically from the next, it’s way easier to remember. With that in mind, we stripped out a lot of stuff from my talk that I didn’t really believe in, or that didn’t flow well, and focused instead on ensuring clarity and simplicity.

To be honest, Kim saw me at my lowest. I wasn’t exaggerating when I said I hate public speaking. But I felt a duty to FIRE to not just do this, but to do it well. A mediocre talk would be a missed opportunity, and a bad talk could be an embarrassing disaster — not just for me, but for the organization I represent and the principles we are out to defend. I had to work my butt off to try to give a great talk, something that would actually reach new people with this important message. After all, that’s what FIRE is all about.

So I kept at it — recording new versions, pacing around D.C. like a crazy person, reciting lines to myself.

All of this helped immensely, but it was still insanely difficult. Even in the final rehearsals — from late March to early April — I was still freezing up, still blowing lines, still totally exhausted by all of it. And all I had to do on the big day was deliver a talk way better than I’d ever done in rehearsal.

Easy, right? Not for me.

Showtime in Vancouver, and my first bit of feedback

Things changed once I arrived at the actual TED conference in Vancouver, Canada. At my final rehearsal, I saw other speakers practicing their own talks and was shocked to discover that some of them weren’t even close to ready. And when someone blew a line on stage? The audience was completely supportive. It suddenly seemed like everyone understood how insanely difficult this all was, and they had your back.

That was a turning point for me. I realized everyone else was human too, and not these perfectly erudite speech-delivering machines. In fact, many of them hated public speaking just as much as I did. All of them were nervous, because we all knew what a big deal this was. And it turns out, the nerves were a good sign. One TED trainer told me that the best talks often come from introverted, intellectually-minded people who work their butts off to make the unnatural look natural. The organizers actually worry more about people who love the spotlight, because they tend to overdo it or overstay their welcome.

Listening to the other talks, I began to wonder if I’d been unfair to TED with my initial reservations. Maybe TED 2025 was just a special cohort, or at least the beginning of a shift away from the reasons why I had been hesitant to join. Whatever it was, most of the talks I saw were incredible — particularly those from John McWhorter’s session, which was called “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” after the movie of the same name. Throughout the conference I made new friends, met brilliant thinkers — and for the first time in a long time, I got to unplug from the “emergency room” pace of free speech defense for a while.

I gave my talk on Wednesday morning. Though I envied the folks who went earlier and got their talks over with, I was glad I didn’t have to wait until Friday. I felt terrible for those people.

At the risk of humblebragging (minus the humble), I was delighted that my talk was interrupted multiple times by applause. This was not what I expected. To be frank, I thought I might be booed. I’ve found that some left-leaning spaces (which I think TED has been, historically) really hate unapologetic defenses of free speech. But the TED audience that day surprised me. They felt like classic liberals still committed to open dialogue, and I found that incredibly heartening. No other talk that week was interrupted by applause as often, which I have to say makes me feel pretty amazing. But the standing ovation I got at the end? I was stunned. I still can’t believe that.

My biggest hope is that this moment reflects a broader cultural shift. Hopefully, this is a signal that more people are ready for a message about freedom of speech that doesn’t apologize or self-flagellate — a message that recognizes speech as one of the greatest engines of peace, prosperity, and progress in human history.

And if you ever get the chance to give a TED Talk, know this: It won’t feel like you rehearsed it dozens of times. It’ll feel like you rehearsed it hundreds of times. And you probably should rehearse it that much. It’s a hell of a lot of work, but I definitely think it was worth it.

I hope you will too.

I also have to make sure to give a few shout outs here to some new friends, some old friends, and many colleagues who gave fantastic talks at this TED conference: FIRE advisors John McWhorter, and Steven Pinker, Lenore Skenazy, Alice Evans, Hamish McKenzie, Roland Fryer, John Mackey, Scott Loarie, and Megan McArdle.

Also special thanks to Perry Fein, without whom I wouldn’t be able to find my own head, let alone manage my schedule, travel, writing, and everything else. And a big thank you to the entire FIRE staff (and especially the Executive Team) who allowed me to prioritize (and obsess over!) working to make this talk turn out as well as it did.

SHOT FOR THE ROAD

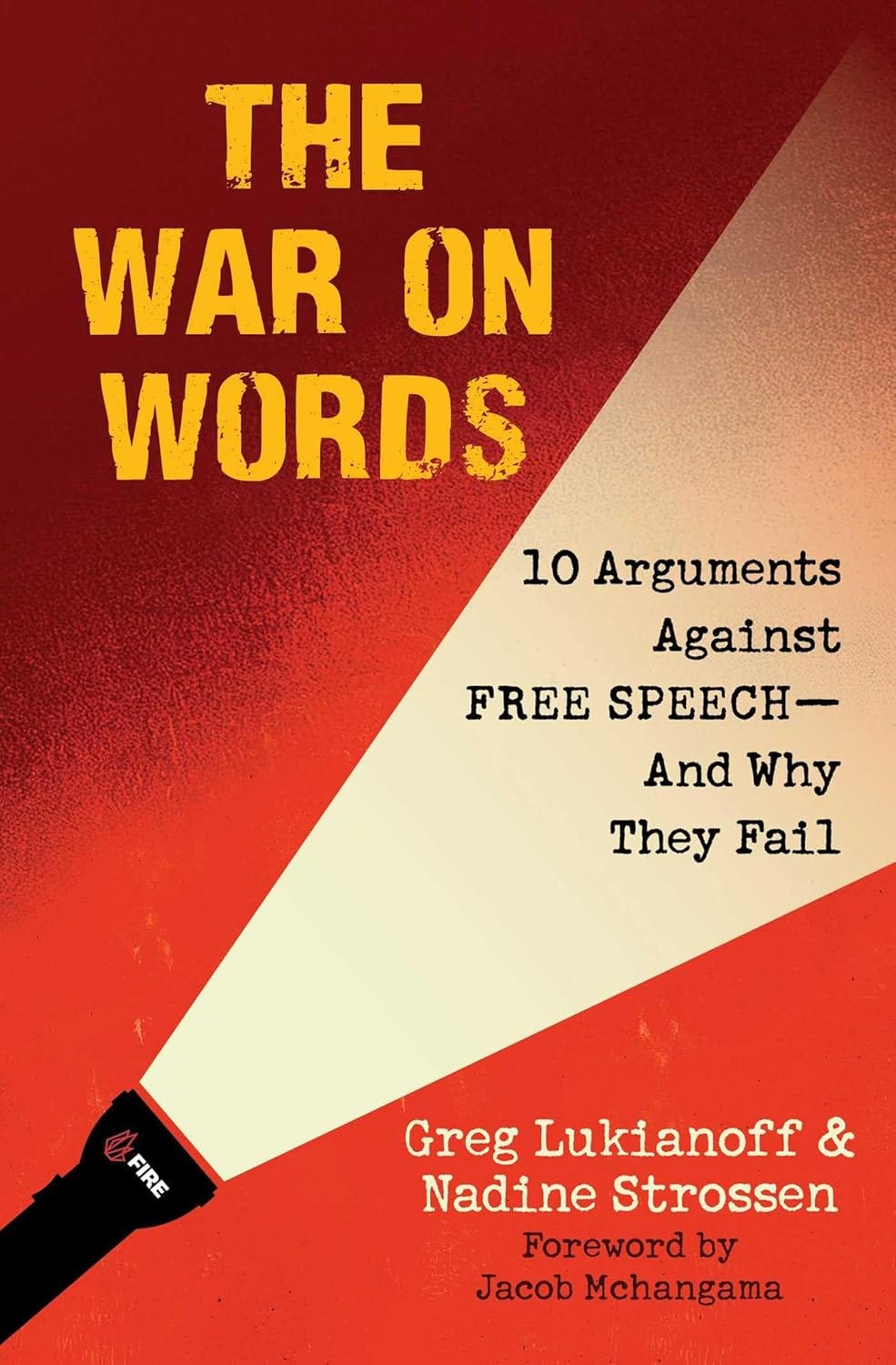

Don’t miss the next ERI Substack Live on July 1 at 4 pm Eastern! I’ll be joined by my dear friend, colleague, FIRE senior fellow, and former ACLU president Nadine Strossen to discuss our forthcoming book, “The War On Words: 10 Arguments Against Free Speech—And Why They Fail” (ebook available today!). Nadine and I will be discussing the book and taking questions from the audience in real time, so make sure to tune in!

Great job, Greg! Either ironic or appropriate that it was given in a country that has hate speech laws and no 1st Amendment.

An excellent talk. Well done! As a Canadian I believe we need this very dialogue in our country but it isn't a focus of public concern. Sadly our Overton Window often seems to be more of a peep hole.