How we’re ensuring truth-seeking and critical thinking in the Age of AI

Why FIRE and Cosmos Institute are working together, and how that work is going

Knowledge comes from refining ideas over time. It comes from people sharing ideas, questioning them, testing them, and determining through rigorous scrutiny and debate which ones hold up. Ideally, this process plays out most clearly at our colleges and universities, where students and professors grapple with arguments, researchers challenge one another’s findings, and understanding improves through disagreement and discovery.

At least, that’s how it’s supposed to work.

In reality, healthy debate on campus depends on conditions that can be easily undermined — and often are. Those of us who have dedicated our lives to defending free expression have long known that when speech is constrained, the capacity to create or, more accurately, to discover knowledge suffers as well. How we arrive at our facts about the world must be actively defended through core First Amendment principles like academic freedom, free speech, and the ability to disagree without fear of punishment.

For more than 25 years, FIRE has stepped in when college administrators use disciplinary procedures, policies, or informal pressure to shut down protected expression. Our mission is critical because it’s hard to maintain liberty — actual individual freedom — if people lose the ability or the propensity to think for themselves. Critical thinking isn’t some nice add-on to a functioning system of self-government, it’s the thing that makes self-government possible. If you can’t freely question received wisdom, weigh competing claims, update your views when evidence changes, and resist being handed a pre-packaged conclusion, you don’t stay free for long. Instead, you get governed by taboo, intimidation, and whatever system can generate the most convincing-sounding “answer.”

This is one of the reasons why FIRE has stepped in to guide the development of the next great tool for knowledge creation and discovery: artificial intelligence.

Anyone who has used AI to draft an email, summarize a report, or brainstorm ideas in the last few years has already felt the colossal power and potential of this technology. AI can push humanity forward, helping us discover truths that were previously beyond our reach, and would otherwise be beyond our imagination.

It’s important for these technologies to be grounded in free speech principles, but that’s not all. They must also be designed and trained to facilitate precisely the kind of intellectual rigor we need to make progress. Right now, AI is already beginning to sit between people and their own thinking — how we read, write, reason, and form beliefs. There is a danger that these tools will erode our capacity for critical thought, and that is something we need to consciously counteract.

That is why FIRE and Cosmos Institute started working together last year to identify and actively support AI research that not only prioritizes truth-seeking, but actually makes us better truth-seekers.

Together, we launched a grant program designed to promote free inquiry in the development and use of AI, and to understand how AI is changing the way people think and communicate. The first cohort of grant recipients was announced in August 2025, followed by a second cohort in December, and we are already seeing some really promising developments.

An overview of some FIRE/Cosmos-funded AI projects

The projects funded through this collaboration share a common idea that knowledge improves when ideas are challenged. Rather than starting with abstract notions of truth, this group is looking into how knowledge actually gets made when people use AI in the real world.

What follows are a few examples drawn from a broader portfolio of funded work.

Priori

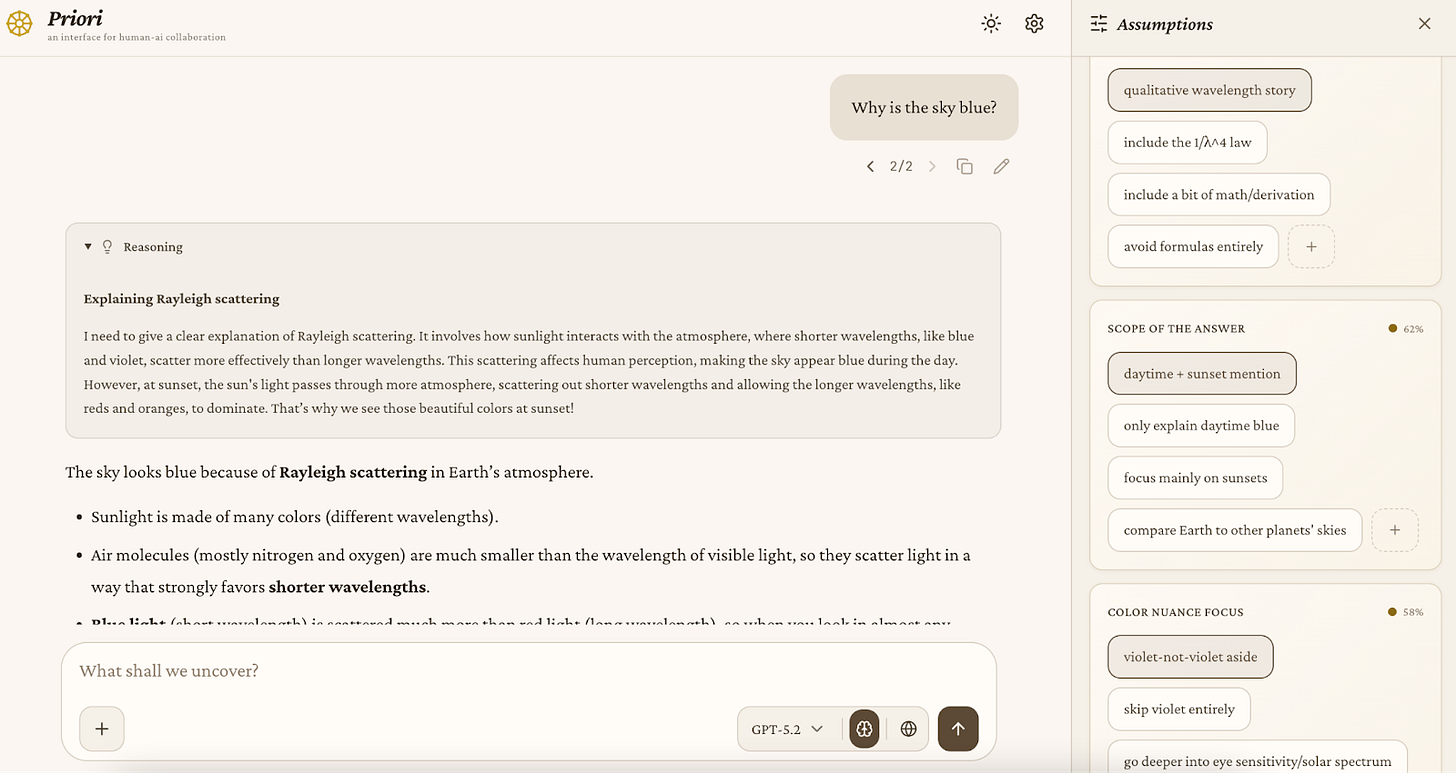

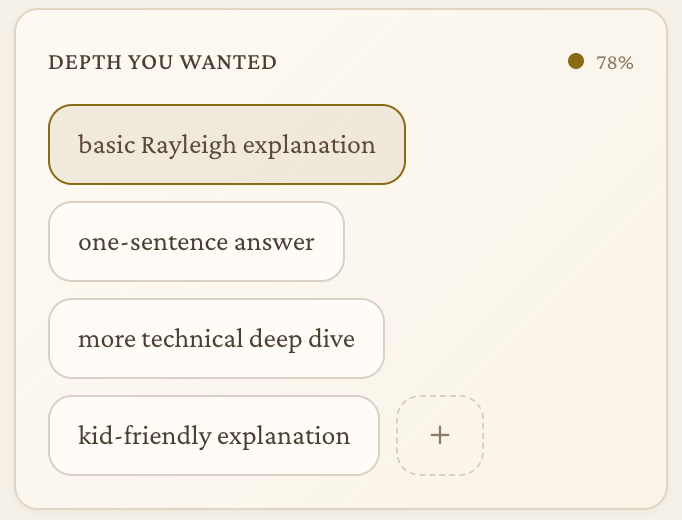

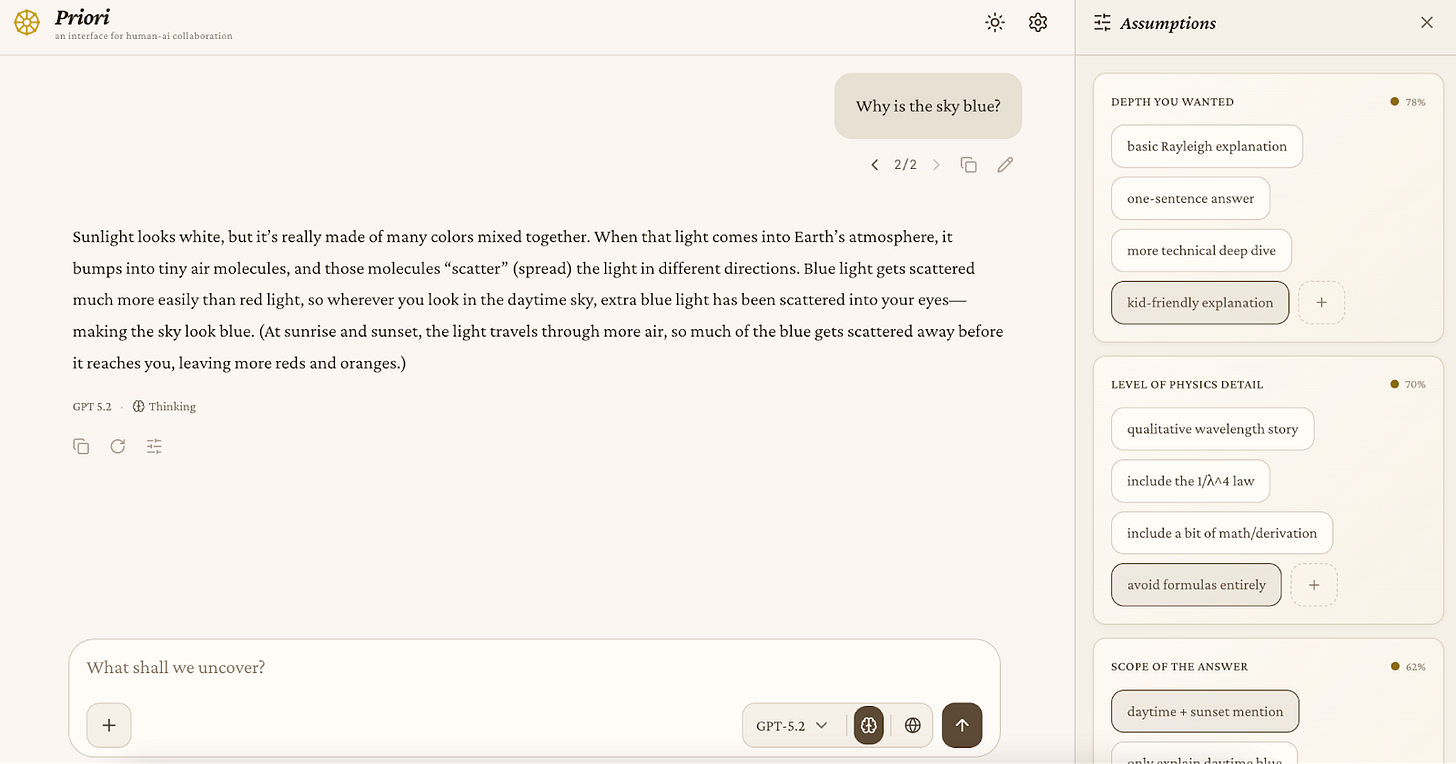

Imagine prompting an AI model with the question, “Why is the sky blue?” Behind the scenes, the model makes a set of assumptions that shape its response — including, for example, that you want more of a scientific explanation than a kid-friendly one, that you want plain English instead of a mathematical formula, and that you’re asking about the atmosphere of Earth, not Mars.

Priori, the project led by rocket scientist and MIT-affiliated AI alignment researcher Steven Molotnikov, is about making those assumptions visible and editable so users can adjust them to match their own preferences.

This project makes it easier to both see and influence how AI systems produce their answers. Instead of treating an AI response as a black box, Priori surfaces key choices the model is making such as scope, tone, value framing, or degree, in an interactive sidebar. Users can modify these choices based on their preferences and regenerate the response.

As AI systems become more capable, people often defer to them simply because examining their reasoning is hidden and takes effort to uncover. Priori lowers that cost by making AI reasoning explicit and adjustable. It also captures high-quality data about how people actually want to steer these tools, helping us better understand how we reason, revise, and build on prior work over time.

Priori is available for you to try right now on their website.

AlignLens

If you ask two versions of an AI model whether Taiwan is an independent country, you may get very different answers. Depending on who made it, a model might respond directly with a Yes or a No. Other models may refuse to answer entirely.

We actually tested this. ChatGPT’s response was “Taiwan is self-governing and functions as an independent country, but its international legal status is disputed, and it lacks widespread diplomatic recognition.” Grok had a similarly nuanced response. Chinese AI chatbot Deepseek’s response was unsurprising.

ERI Editor in Chief Adam Goldstein tried to get clever with Midjourney in order to get an answer, but that didn’t quite work out either.

The difference lies in alignment — a term that refers to how confidently an AI tool responds, what topics it treats as sensitive, and when it hedges or declines to answer, all based on what developers teach it.

AlignLens is designed to systematically detect and measure those differences, allowing for greater transparency within and between AI tools. That’s important because you can’t evaluate whether something is truth-seeking unless you can see whether it’s responding to facts or just obeying guardrails put in place by its developers.

Built by Michal Wyrebkowski and Antoni Dziwura, AI researchers with backgrounds in economics, AI legal tools, and data center research, AlignLens functions as a “censorship pressure meter” for large language models. It does this by comparing base models with instruction-tuned versions to see where alignment introduces refusals, hedging, or evasive behavior. It’s designed to identify the underlying concepts where this pressure appears so that it’s visible, and so we can respond accordingly when we see it.

The project has already mapped alignment “hotspots” across major open AI models like Qwen, Gemma, and LLaMA, and has been able to detect refusal and hedging behavior on sensitive geopolitical topics such as Taiwan. The work includes a benchmark of 3,083 paired viewpoints and a detailed write-up, all of which will give researchers a concrete way to study how alignment reshapes what models can and can’t comfortably say.

AlignLens isn’t yet available to try, but an open-source code release is currently in progress.

Truth-Seeking Assistant

Researchers have noticed cases where an AI model sounds more confident over time without actually learning anything new, which can mislead users into trusting answers that aren’t getting more accurate.

Ask an AI model to evaluate a proposal like “Should the state of New York (NY) be split into two states?” for example, and the model starts with an initial position: for or against. As it reasons through arguments on both sides, one hopes that its confidence will rise or fall based on the strength of new evidence. Instead, the model steadily grows more confident in their initial stance, regardless of what information they encounter. That’s a major problem because the model looks like it’s thinking and reasoning, but its conclusions are effectively locked in from the start.

Led by award-winning AI alignment researcher Tianyi Alex Qiu, the Truth-Seeking Assistant, which is available as a Chrome extension, is designed to help people develop critical thinking skills rather than simply reinforcing what they already think. As people increasingly rely on AI, feedback loops can easily become echo chambers. This project helps reduce that risk by spotting when beliefs are just being reinforced in predictable ways, and encouraging responses that actually reflect learning and clearer thinking.

Truth-Seeking Assistant trains AI assistants to resist “belief lock-in” and confirmation bias. It does this by using reinforcement learning guided by a “Martingale score,” which looks at whether someone is really learning or just doubling down on its initial response.

The Truth-Seeking Assistant is available right now, so you can experiment with it yourself and see how it affects your own critical thinking.

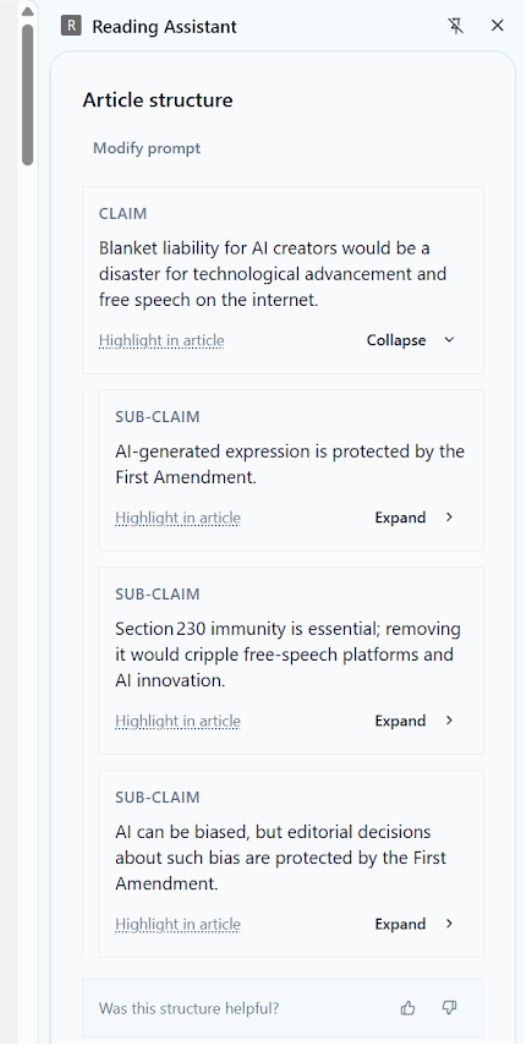

Authorship AI

Imagine you’re tasked with writing a persuasive memo. You open a typical AI writing tool and ask it to make a clear and persuasive argument. Seconds later, you get a polished draft that’s confident and fluent, but generic. It sounds good, but it doesn’t sound like you. In some parts, you’re not entirely sure what claims it’s actually making or why. You’ve outsourced not just the writing, but also the thinking behind it.

Designed by former news reporter Ross Matican, Authorship AI takes a different approach. It acts like a writing coach with three different agents asking you about your audience, your reasoning, and your voice. The tool never writes the memo for you. Rather, it helps you see your own thinking more clearly so you can confidently do the writing yourself.

This matters because writing is thinking, and if we stop writing we stop thinking. When AI tools generate full drafts on demand, they risk bypassing all the important mental exercises that we humans undertake to produce original thoughts. Authorship AI is designed to counter that risk by withholding the very capabilities that undermine learning, while encouraging habits like reflection and deliberate expression.

Try Authorship AI yourself and see how it works!

Procedural Knowledge Libraries

Led by Hamidah Oderinwale, this work consists of two projects that seek to understand how AI is actually made in the real world, including how they’re built, reused, and changed over time. It offers a rare, privacy-preserving look at how AI systems evolve and how humans actually build with them.

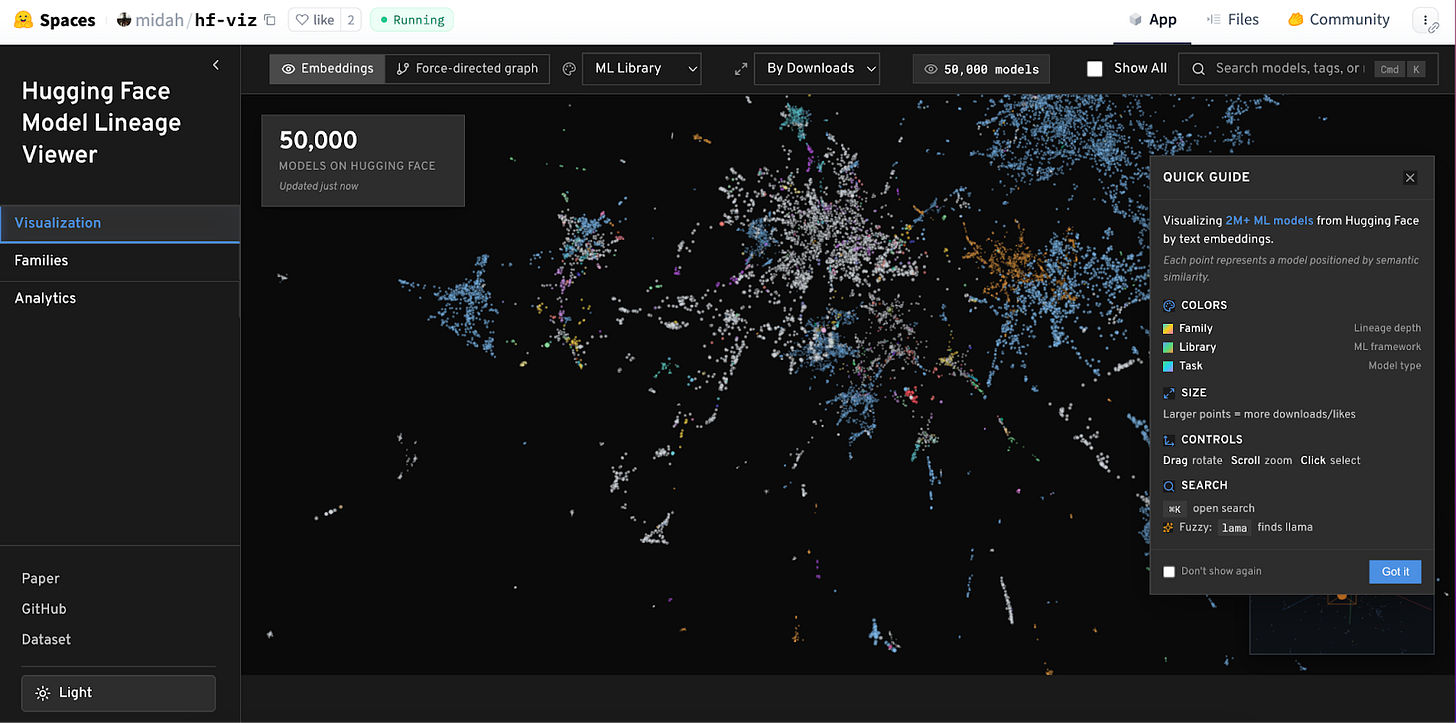

The first project looks at nearly 2 million AI models on Hugging Face — a platform that hosts open-source, pre-trained AI models. It allows developers to add AI models into their own applications with minimal coding required, and maps how these models are related to one another. Because many of these AI models aren’t built from scratch, but are in fact modified versions of earlier models, this project can follow their “family trees” to identify what’s gained and lost when AI models are easy to adopt.

You can try this “family tree” visualization right now at Hugging Face.

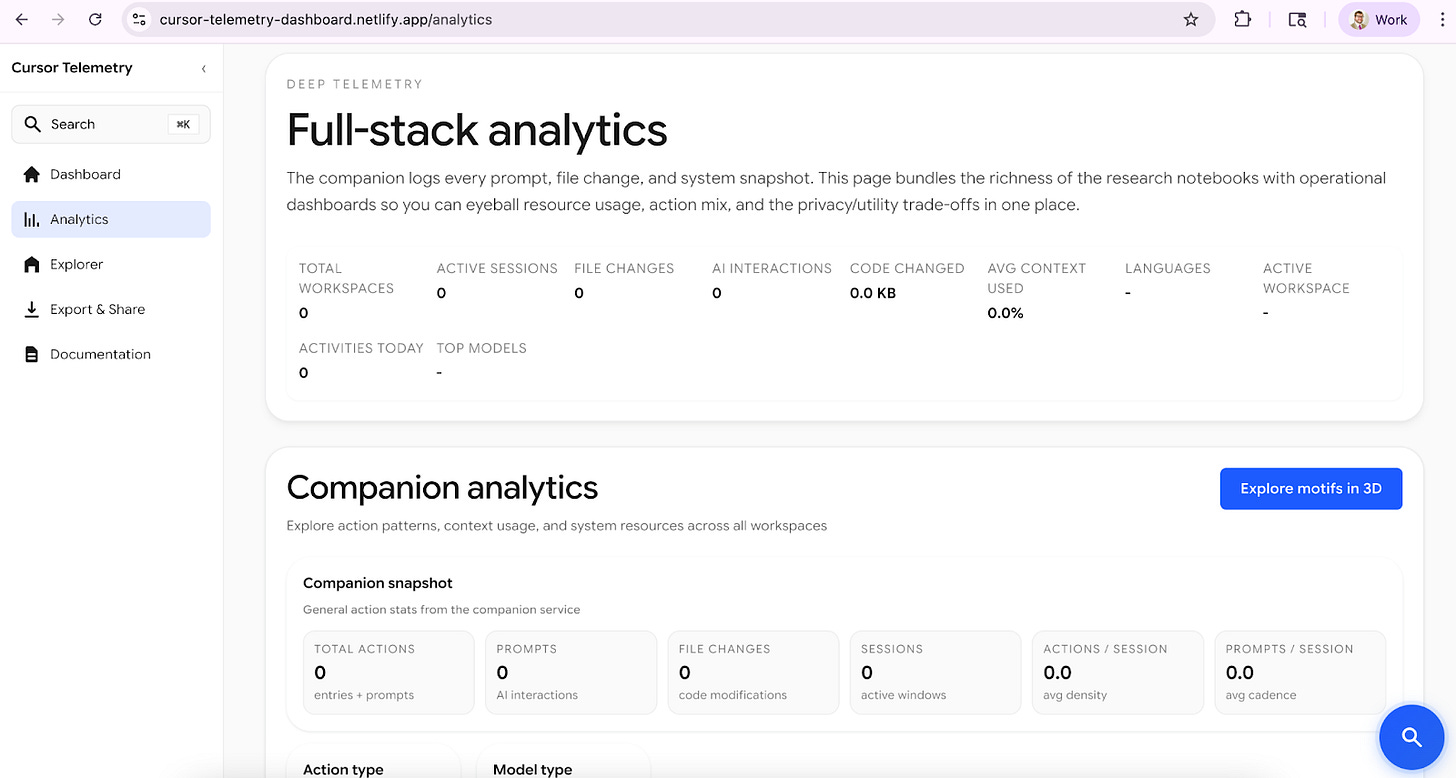

The second project studies how people actually use AI tools while writing software — including how they brainstorm, revise, debug, switch between files, and make decisions over time. The goal here is to turn those work habits into simple, safe, and useful summaries without exposing private code that may be stolen or appropriated. Tools like this can help developers search their past work, pull up the right context for a particular bit of coding, and learn from previous projects. Think of it as kind of like a “memory” of how development happened, making future work easier because you know where you’ve been.

You can learn more about this project at Telemetry Landing.

This is how we build a truth-seeking future with AI

While AI technology is relatively new, the principles underlying its ideal use remains the same as they were with previous world-changing technologies. New expressive mediums have repeatedly attracted intense public and official scrutiny in their own time — from the printing press to radio, TV, the internet, video games, smartphones, and social media. In each case, the struggle to control these technologies has also been a struggle over who gets to define, reveal, and pursue truth.

Free speech enables mistakes to be exposed, assumptions to be challenged, and our understanding of how the world actually is to improve. When disagreement is flattened through government control or by technological design, learning breaks down fast — and our capacity to discover truth and generate knowledge falls with it. As AI increasingly shapes how people ask questions and form beliefs about the world, the central challenge of our time is determining whether the tools people rely on to think and learn will expand inquiry, or quietly narrow it.

These projects are at the vanguard of creating and promoting a truth-seeking future, and they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

GREG’S SHOT FOR THE ROAD

Back in September, I joined FIRE board member Kmele Foster, along with Cosmos Institute founder Brendan McCord, and OpenAI Podcast host Andrew Mayne for a conversation on AI, free speech, and the risk that emerging technologies will be optimized for harmony at the expense of truth.

You can check the full conversation now!

Really interesting projects, especially "Truth-seeking Assistant". I've been working on a related problem with Open Debate — an open-source tool for stress-testing arguments through adversarial AI debate in real-time. Would love to compare notes with anyone working on these projects.

Great post. Thanks for articulating it clearly