Deeper into defining 'Cancel Culture' with Scott Alexander

Scott's response to Greg and Rikki's definition brings up great questions worth addressing

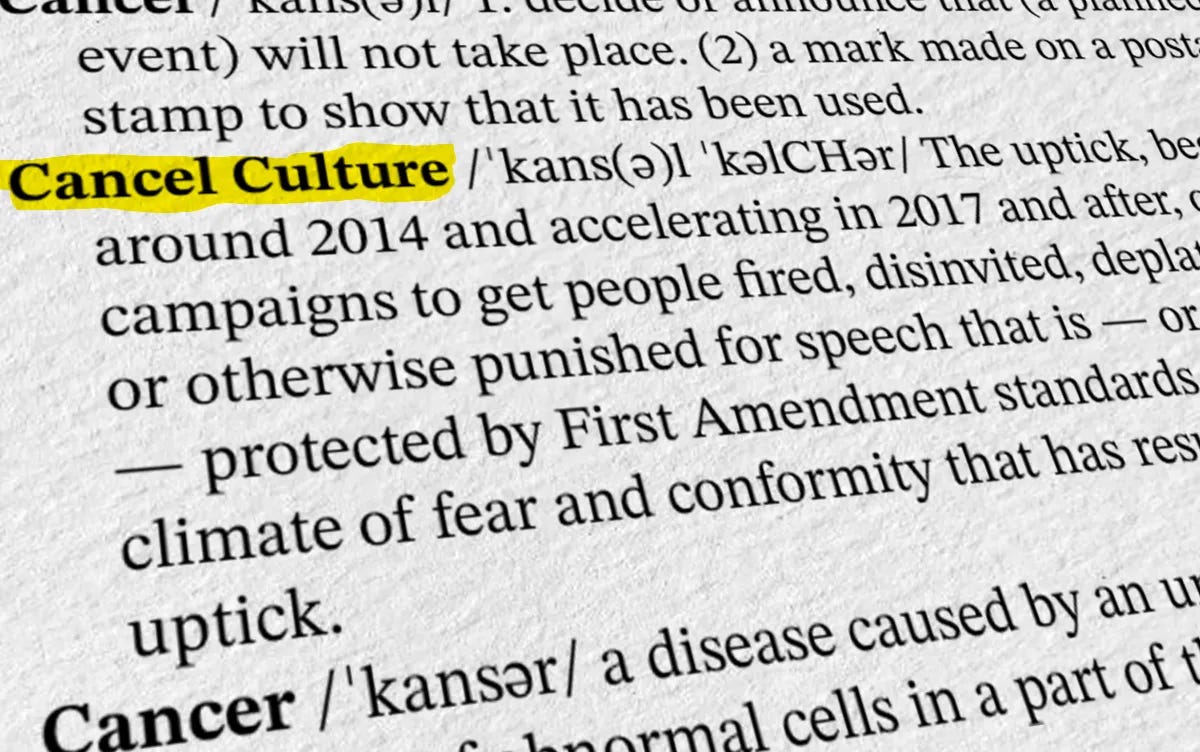

We were excited to see that Scott Alexander responded to Greg and Rikki Schlott’s definition of “Cancel Culture,” which comes from their book “The Canceling of the American Mind.” Here we have broken it down into its four key elements.

Cancel Culture is the

uptick, beginning around 2014 and accelerating in 2017 and after, of

campaigns to get people fired, disinvited, deplatformed, or otherwise punished for speech that

is — or would be — protected by First Amendment standards, and

the climate of fear and conformity that has resulted from this uptick.

It’s very important that people are thinking and talking about this, because we can’t change this behavior until we can see it clearly. Alexander in particular has been fighting Social Justice Fundamentalism (SJF) since the very early days of Cancel Culture on the pre-Cambrian social media site Tumblr, and more recently pushed back against what amounted to his being doxxed by The New York Times.

In his response to Greg’s post outlining the benefits of his and Rikki’s definition, Alexander said that he was looking for something more rigorous, and asked how our definition might handle a number of philosophical thought experiments. If we unpack our definition a bit more, we can see it’s more rigorous than it might have seemed at first. Part of the goal of this definition was to come up with a short(ish) definition that encapsulated a great deal of meaning without having to be pages and pages long, and we think we've achieved that.

In particular, there are the first three parts of the definition that, given the proper emphasis, resolve the questions he raised. And there’s one thing that isn’t in the definition that we’d like to reflect on, too, for clarity’s sake.

‘Or would be’ refers to the principles underlying First Amendment precedents.

In his response, Alexander asks whether we were advocating for First Amendment standards to apply to private businesses. (If he’s confused, then we probably confused a lot of other people, too!)

We absolutely are not arguing that the First Amendment applies to private businesses. In fact, private businesses have their own First Amendment rights, and we would never want those rights taken away. We are, however, saying we can draw guidance from the First Amendment when we determine how to react to the speech of private employees, by applying the underlying logic and philosophy from our well-developed common law tradition. We don’t think people should view the case law as dispositive in these scenarios, but as standing in for wise principles that could be applied to the same situations. In other words, allowing the logic undergirding First Amendment jurisprudence to guide us when the law doesn’t apply.

As Greg noted in his initial response to Alexander (which breaks this down in much more detail), the First Amendment is realistic about what different jobs entail. For example, the Pickering-Connick test says that when a public employee speaks on a matter of public concern, the court should weigh the right of the speaker against the need of the employer to have an efficient and disruptive-free workplace. That doesn’t apply to Home Depot, a private employer. However, we can take the underlying principle of Pickering-Connick and restate it as a common-sense list of principles. When an employee comments on (1) a matter of public concern, (2) on his or her own time, and (3) that comment doesn't prevent that employee from carrying out their job generally, they should be allowed to do so without losing their job.

If we agree that having strong political opinions off the clock is not necessarily a limitation on the ability to scan tools and appliances at a checkout counter, we should approach calls for firing a Home Depot employee for their political speech with skepticism, at the very least. Not because the law says so, but because there are good philosophical reasons why that should be so (and those reasons happen to be reflected in our common law).

To be really clear, we’re not saying that we should treat private employers as if the First Amendment applied to them. When a situation comes up where, for example, someone loses their job for writing an op-ed or tweet as a private citizen, in their free time, on a matter of public concern, we don’t think the answer is to automatically say, “oh, the First Amendment prohibits firing public employees for this, so it should also be prohibited here.” But we should remember the underlying concern of the First Amendment: Without it, public employees would only have free speech in the most technical sense. They could exercise their free speech or have a job, but not both.

If we apply the logic and philosophy that undergirds the First Amendment to the private employee, we have a pretty persuasive argument that it's societally harmful to fire that employee. That’s even more true if you think beyond the individual case and extrapolate the outcome to every private employee who speaks on their own time. If everyone would get in trouble if they didn't toe the political or ideological line set by their employer, only employers would have free speech. What would the world look like then? What would be left of free speech?

And yet, Pickering-Connick only gives us a baseline rule. Other cases introduce nuances that go well beyond the standard public employee situation. For example, Garcetti v. Ceballos makes the pretty common sense point that if your job is to be a spokesperson and you embarrass your company or boss by saying something stupid online or in public, it's understandable that someone might evaluate that somewhat differently than they might if you were just an average Joe employee.

Again, we're not saying that case law is dispositive. We’re saying that it's based on some really sound analysis that makes just as much moral and philosophical sense outside of the situations in which following it is mandatory. It’s not about applying the First Amendment rigidly or even by analogy, it’s about the principles that drive First Amendment case law, and using that guidance to resolve speech disputes in other contexts.

The word ‘campaigns’ is an essential part of the definition.

“Campaign” refers to a concerted activity. Individual choices, even if they end up being the same and large in number, would never amount to a campaign. A collective and concerted effort to sanction a podcast or deplatform a speaker so that no one else can listen to it, even if they want to, would meet that standard.

Alexander’s response queued up a number of scenarios that would not meet that standard, such as choosing not to listen to a podcast, or saying others shouldn’t listen to it. In fact, the vast majority of his hypotheticals are knocked out by the word “campaign” alone.

The grayest area might be the scenarios where someone makes public statements that suggest no one else should make the same personal decision — but until that view is given action by an attempt to convey it to the speaker’s employer, even that is still not a campaign. For this reason, none of the examples Alexander lists in his response would constitute Cancel Culture, except the two that involve contacting the podcast host to deplatform the speakers or starting a campaign to do the same. (Some of the others, like doxxing attempts, may be “Cancel-adjacent,” but “Cancel Culture” isn’t and shouldn’t be a catch-all term for all repulsive culture war behavior.)

This also means that a collective rejection of something on the basis of its expression is not cancelation, even if it results in firings. If you’re in charge of marketing for a brand, for example, and your advertising directly alienates your core audience, your inevitable termination won’t be due to your speech but rather your poor job performance. You can have situations where there are failed attempts to cancel someone that only fail because that person is already terminated for cause.

For a good example of what constitutes a campaign, we can look to Jonathan Rauch’s definition of Cancel Culture, which Greg referred to in his response to Alexander but didn’t extrapolate on (though we have discussed it in the past).

Rauch’s factors:

Is the goal of the critics punitive?

Is this de-platforming?

Is the effort organized?

Are there secondary boycotts? For example, are there calls to punish people who don’t immediately fall in line?

Is there moral grandstanding?

Are the allegations more truthiness than truth? (To put this in more specific terms, are the allegations relying on generalization or abstraction in such a way as to obfuscate the underlying allegation?)

At a minimum, anything that fulfills any two of these criteria and doesn’t contradict any First Amendment standard should be viewed as an example of Cancel Culture.

So why not just use Rauch’s definition all the time? As Greg noted in his previous post, as powerful as Rauch’s formulation is, it requires a fair bit of knowledge about the finer points of an incident, which may not always be readily available. Certain aspects of Rauch’s breakdown, like knowing the goals of critics, might never genuinely be known at all. But we do think that combining our definition and Rauch’s can really help folks hone in on what is (and is not) Cancel Culture.

‘The uptick’ clarifies that this is about the frequency of cancelation attempts, not necessarily any individual cancelation.

There’s a benefit to highlighting difficult hypotheticals and thought experiments when trying to zero in on a concept or underlying moral rule, as Alexander does in his response to Greg’s definition. However, focusing on fringe cases can also cause us to miss an important part of Greg and Rikki’s definition: Cancel Culture is about the rise in attempts to cancel people, not the mere existence of those attempts. Things we would define as cancelations existed prior to 2014, but there were far fewer of them, and the threshold was much higher. Tumblr hadn’t yet weaponized relational aggression in a way that could make a cancelation mob coalesce instantly (just add torches and pitchforks!).

As Greg noted in his response to Alexander (we just think it would be harder to state better than this!):

This behavior, at this scale and velocity, was simply not possible before. And again, 2014 isn’t an arbitrary starting point. Focusing on college campuses for a moment, there have been more than 1,000 professor cancelation attempts since 2014, with two-thirds resulting in some form of sanction and one-fifth resulting in termination. That’s 200 professors who were fired or forced out. As we’ve mentioned many times before, this is twice as many as the standard estimate of professors fired during McCarthyism, more than three times as many as the professors fired for being communists, and — importantly — without any meaningful historical comparison, since First Amendment law that strongly protects the freedom of speech rights of students and professors was only established between 1957 and 1973.

To be clear, what we’re saying here doesn’t mean the edge cases don’t deserve attention. But it’s impractical to build a coalition around edge cases. We’ve been doing this kind of work at FIRE for 25 years, and we know that you can’t persuade people on every case. People do factor in offensiveness in their determination of what is and is not Cancel Culture, even if our definition doesn’t (more on that below). Indeed, even the law factors in offensiveness when it comes to patterns of behavior like harassment. However, it tries to cabin the potential excessive subjectivity of such a determination by requiring that a harassing pattern of behavior be both offensive to the individual it's directed at, and offensive to a reasonable person under those circumstances.

It wouldn’t necessarily be a problem for democracy if people thought that some cancelations were appropriate. And if someone believes that, they should own what they’re saying: That someone was canceled in an instance of Cancel Culture, and they believe it’s okay. The problem is twofold: the sheer volume, and the increasingly sensitive trigger for it.

At the same time, if we can get to 80% or 85% agreement on what Cancel Culture looks like, that’s progress and will help with the supermajority of cases. The fact that the right and left won’t agree on what of that 15-20% goes too far in terms of offending their norms doesn’t change that.

One thing that isn’t in our definition of Cancel Culture is the content of the speech.

It’s important to clarify that content we dislike doesn’t necessarily make a particular Cancel Culture case difficult.

We raise this because many of Alexander’s hypotheticals involved discussion of pedophilia — presumably because the public is nearly universally repulsed by the topic and this would illustrate the difficulty of pushing back against behavior set against it. But disgust is not a basis for censorship under the principles of the First Amendment, and that alone does not make something an edge case. Indeed, FIRE had two cases of professors canceled for discussing pedophilia within their academic disciplines.

To use one of our own cases as an example, when Old Dominion University put a professor on leave following an interview where they explained their book’s attempt to distinguish between “minor-attracted persons” who don’t act on their impulses but need treatment, and the sex offenders who do act on those impulses, it was a clear case of Cancel Culture. It met the time window (between 2014 and now), Walker was subject to multiple threats, and there was a petition with over 15,000 signatures calling for their termination (a campaign).

This was a state school, so it turns out that the First Amendment applied directly to the situation, but even if that weren’t the case we could still imagine how the principles of the First Amendment would apply here. What does the case law say about academic freedom in this context? Our nation is “deeply committed” to academic freedom (Keyishian), teachers must be “free to inquire” so that our nation does not “stagnate and die” (Sweezy), and even other public employee tests recognize the special case of professors and academic freedom (Garcetti).

FIRE’s principled stance in favor of free expression would never waver based on the content. As we’re quite fond of saying: If it’s protected, we defend it. No throat-clearing. No exceptions.

But while we fully embrace our role as watchdog, we also recognize that you're not necessarily going to get everybody in a given society to even agree with you on all of the edge cases. So again, if we can get people to 80% agreement, that's probably about as good as you're going to do unless you're a bunch of weirdos like those of us at FIRE.

The good news is that fringe cases are rare.

It seems like there is broad agreement over Cancel Culture as a problem, even if it’s been difficult to pin down exactly how we should define it. As we continue these conversations going forward, it’s good to know we have serious and principled thinkers like Scott Alexander helping us return the culture to one that respects free expression and responds to ideas with other ideas.

Alexander compared Cancel Culture to obscenity, in that “we know it when we see it,” and we agree. For people still confused, there are plenty of extended examinations of specific cancelations across various fields in Greg and Rikki’s book “The Canceling of the American Mind,” which we highly recommend everyone read if they haven’t already.

In the meantime, here are some examples of things that are Cancel Culture, by our definition:

January 2020: Babson University fires adjunct professor and staff member Asheen Phansey after a Facebook post with a joke. President Trump had tweeted a warning to Iran that if they took action against the United States, the U.S. had a list of 52 sites, including cultural sites, it could strike within Iran. Phansey’s joke: “In retaliation, Ayatollah Khomeini should tweet a list of 52 sites of beloved American cultural heritage that he would bomb. Um… Mall of America? … Kardashian residence?” People called on others to contact his employer, meaning there was a campaign against protected speech (a joke unrelated to his job) to get someone fired for that speech.

September 2020: Taylor University fires philosophy professor Jim Spiegel for a video he uploaded to YouTube. Spiegel uploaded songs, and this one, “Little Hitler,” was about humanity’s propensity for evil and how everyone has a “little Hitler” inside of them; for example, one line says “You may be smiling on the outside, but inside, you’d love to see me dead.” Spiegel’s termination letter says an anonymous co-worker contacted the school to complain — a very small campaign, but a campaign nonetheless — in an effort to have Spiegel punished for his protected speech.

January 2021: The University of Central Florida attempts to fire professor Charles Negy after a six-month investigation into 15 years of his teaching. The investigation was launched because some students complained (or perhaps we should say, campaigned) to the school that they didn’t like Negy’s tweets. When the college initially balked at punishing protected private speech, the students claimed Negy’s Twitter account was required reading, and thus classroom speech. The report found that was untrue, but the college tried to fire Negy anyway. Because a student campaign to punish Negy for his protected social media speech led to a professional sanction, this is a clear example of Cancel Culture.

July 2022: Minneapolis venue First Avenue cancels Dave Chapelle’s show after public backlash following the show’s announcement. Social media comments and a petition criticized Chapelle’s prior jokes as transphobic and called on the venue to cancel the show. Two days after the petition was started, First Avenue management posted that they work to make their venues “the safest spaces in the country,” canceled the show, and said that ticketholders would be refunded. Looking at our definition, a campaign called for the deplatforming of a comedian on the basis of his speech, and the speech didn’t violate the First Amendment; that’s Cancel Culture.

January 2023: Carole Hooven resigns from Harvard. In the prior semester, no graduate students would agree to serve as teaching fellows for her courses. Hooven had been called out by DEI administrators on social media after she gave an interview saying it was a mistake for medical schools to move away from terms like “man” and “woman.” While Hooven’s opinion was related to her work, the principles underlying First Amendment precedent about academic freedom suggest that a professor, even one employed at a private institution, should be given the maximum possible freedom to speak and research as they see fit. For using her academic freedom in that way, Hooven was targeted and ultimately constructively terminated via a hostile workplace.

February 2024: Two venues cancel sold-out shows by rapper Matisyahu, citing security and staffing concerns. Matisyahu has been targeted for supporting the right of Israel to exist, despite being a strong supporter of human rights independent of statehood. Matisyahu had even offered to pay for additional security and staffing at one of the venues, and the offer was refused. Because a campaign called for the deplatforming of an artist for his protected speech, Matisyahu’s canceled shows are instances of Cancel Culture.

February 2024: Indiana University cancels the planned career retrospective of 87-year-old Palestinian artist Samia Halaby. Halaby says she was initially told it was due to complaints about her social media activism, then later told that security concerns drove the decision. Whether it was complaints from museum employees (a direct campaign) or the argued inability to protect Halaby’s works from an angry crowd (the “heckler’s veto,” or a campaign of intimidation), the deplatforming had the desired effect, and is an example of Cancel Culture.

As we mentioned, there are many more examples of real Cancel Culture in “The Canceling of the American Mind,” including how it drove a friend of Greg’s to suicide.

And here are three examples of things that aren’t cancel culture:

July 2017: Anthony Scaramucci was fired halfway through his second week on the job as White House communications director. While Scaramucci was fired for his speech — he gave an interview where he attacked then-Counselor to the President Steve Bannon and then-recent Chief of Staff Reince Priebus — Scaramucci was hired as a spokesman for the administration. When he started attacking his co-workers, he went rogue, and that’s exactly the situation where the First Amendment won’t protect a public employee (at least, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in Garcetti v. Ceballos, as discussed above).

February 2019: Jussie Smollett is written out of the fifth season of “Empire” after his reports of being a victim of a hate crime the month prior fell apart. Smollett wasn’t canceled, he was caught lying about being a victim of a race-motivated crime. This — lying about having a crime committed against you, and as a result wasting police resources on an investigation into it — is itself a crime. Smollett’s behavior is made even more egregious by the fact that he did this during a time when racial tension was rising. Nobody liked that. Actors are brands, and a mass decision to disengage from a brand when it disgusts you isn't a campaign. And when a TV show or producer fires you because you’re harming their bottom line in that way, it isn’t Cancel Culture.

August 2021: A hashtag campaign, “#MuteRKelly,” sought to get the R&B artist’s songs exiled from airwaves. But R. Kelly wasn’t being targeted for having the wrong opinions, using the wrong words, or telling the wrong jokes; he was targeted for decades of allegations of sexual abuse that would earn him a 30-year prison sentence ten months later. (You could say the same thing about Harvey Weinstein, Danny Masterson, or any one of probably, sadly, dozens of other once-household names.)

The success of a coalition to oppose Cancel Culture won’t be defined by fringe cases. At its core, free speech culture is about tolerating difference; so the ability to disagree about fringe cases and still work together is the great virtue of free speech culture over its alternatives. If, for reasons of conscience or uncertainty, not everyone pulls in the same direction on every individual case, it shouldn’t stop us from fixing the problem overall.

One way FIRE is trying to help stop Cancel Culture on campus is factoring how colleges react to it in our College Free Speech Rankings. The 2025 rankings come out next week, and schools that don’t defend their professors lose points (the vast majority of the score is the world’s largest survey of campus free expression).

Keep an eye out for that!

In the meantime, we want to thank Scott Alexander once again for engaging in this topic so thoughtfully, and for giving us the opportunity to dig deeper into our definition of Cancel Culture so we can, hopefully, all achieve more clarity.

Shot for the Road

For a deeper dive into themes from “The Canceling of the American Mind,” check out my interview on The Lex Fridman podcast.

The best defense is a good offense. I'd like to see counter suits in cases that merit them.

Hmm... Was thinking this post was clear and excellent until:

"February 2019: Jussie Smollett is written out of the fifth season of “Empire” after his reports of being a victim of a hate crime the month prior fell apart. Smollett wasn’t canceled, he was caught lying about being a victim of a race-motivated crime. This — lying about having a crime committed against you, and as a result wasting police resources on an investigation into it — is itself a crime."

Was there a campaign? Is it because of a campaign that the bottom line might have been affected? If there was a campaign then wouldn't that meet your definition of cancel culture? Surely a campaign to "cancel liars" or even criminals is still cancelled culture.

I can see you might argue how it is a core part of the job. Actors are brands afterall, but as written you don't lead with that, or make it clear that that is why this isn't an example of cancel culture. The fact he is a liar is complete red herring, and distracts from the clarity of your point.

Thinking further I think the distinction you see here is that the "cancellation" is based on you interpreting them being cancelled for lying as different from them being cancelled for speach. I think such a distinction needs elaboration. Would cancelling Trump be fair game as he has lied? Should media platforms like twitter be allowed to pressured to deplatform trump because of that? Etc...